Veerabhadra Temple and Lepakshi: Where Sculptors Breathed Life into Rocks

I am back from the beautiful Veerabhadra Swami Temple in Lepakshi in the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. Built by brothers Virupanna and Veeranna during the period of the Karnataka Empire (called Vijayanagara Empire by some historians), the temple complex contains some outstanding rock carvings. The brothers were Nayak chieftains reporting to the king (Achyuta Deva Raya).

I’ve not yet visited Hampi, which might be a good thing. Lepakshi is said to be a gateway to the bigger artistic masterpieces in Hampi built in the same style. Perhaps, I would not have appreciated Lepakshi if I had already seen Hampi.

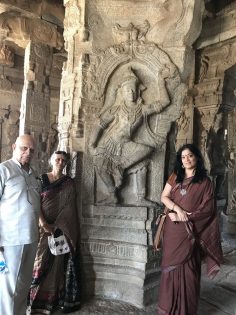

What would I not do to get 15 minutes in that era when the dance hall was used by classical dancers to present their art to the deities of the temple. All the carvings would have come alive! Inside the Natyamandapa (dancing hall) are figures of Apsaras like Rambha and various deities, all carved with exquisite perfection that comes from deep devotion. Some are damaged because of the destruction wrought by the Bahmani Sultans whose hatred for what they called idolatry made them blind to divine art.

In India, this destruction has usually been discussed in hushed tones for fear of reprisals but the times are changing. Still, this temple is comparatively less damaged than Hampi, said our guide who was himself named Virupanna. “You will weep when you see the destruction in Hampi!”

The presiding deity of the temple is Veerabhadra who is none other than Shiva in his fierce form — the one who will not tolerate any insult or distress caused to his dear wife Parvati. The priest did a wonderful aarti to the deity and answered some questions put by me. My mother whispered to me that the gentle, kindly style in which he spoke was characteristic of people from Hindupur. “Just like my mother,” she said.

No photography was allowed inside the main temple area and I didn’t even want to take pictures there. Instead, I gazed long at the murti of Veerabhadra to fix the image in my mind. The problem with the era of photography is that we forget all those moments when the camera was off and the mind just remembers the photo moments.

I loved that there were two lingas, one in Vaishnava style with lotus carvings at its base and the other in Shaiva style, both facing each other in order to show the unity of Shaiva and Vaishnava traditions. There were also murtis of Parvati and Durga dressed in beautiful sarees.

I saw the carving of the famous lady of the Padmini jaati who had all the mathematically prescribed physical features of a classical beauty. The distance from the top of the forehead to the beginning of the nose had to be equal to the length of the nose which again had to be equal to the distance from the base of the nose to the extremity of the chin.

In other words, a perfect oval face was the standard. The length of the face had to be equal to the distance from the chin to the centre of the breasts which again had to be equal to the distance from the breasts to the waist. The arms had to be thin and the fingers had to be long.

There was also a rock-cut relief of the perfect man. Broad shoulders, long arms that can almost touch the knee (Ajanabahu), symmetrical face; in other words, someone who you wish could step out from the pillar and dance with you.

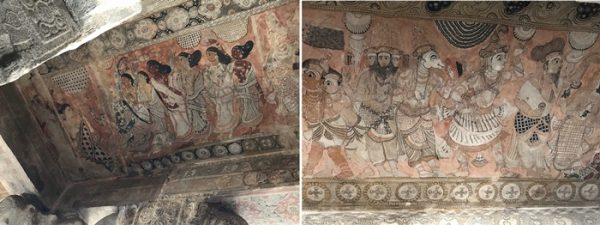

The Veerabhadra temple also has very well-preserved ceiling paintings.

An interesting carving that the guide pointed out to me was of a Chinese man. Chinese traders often came to do business during the reign of the Karnataka Emperors. Shaking his head in disapproval, the guide said the Chinese got diamonds in return for the paltry perfumes they brought. Precious stones were available in profusion in the Empire and it is said they were even sold alongside vegetables in open markets!

The hanging pillar was, of course, the star attraction for tourists. The guide slid a handkerchief under the pillar to show us how it was not touching the ground except at one corner. He explained that it was actually a perfectly hanging pillar until the British archaeologists tried to find out how it was supported so perfectly and in the process, they dislodged it causing all the pillars to tilt. He explained that if anyone tried to straighten the hanging pillar today, everything would collapse.

It is not hard to figure out why the pillar would have been hanging perfectly before the British meddled with it. The excellent interlocking system at the top of the pillar combined with the fact that so many other (non-hanging) pillars are sharing the load of the roof slab would have ensured that the pillar stood straight. Whether this was done intentionally or whether the floor got separated from the pillar due to settlement is something we might never know.

My eyes popped out of my head when I saw the Kalyana Mandapa or the marriage hall of Shiva-Parvati which is incomplete and yet outstanding. The pillars in the hall which is open to the sky have carvings of all the invitees to the Shiva-Parvati wedding — Indra, Vasishta, Brihaspati, Vishvamitra, Vayu, Yama, Varuna, Agni and Kubera. My eyes dwelt for a little bit on how Shiva and Parvati were holding hands. How meaningful!

There is a gory story of how the mandapa could not be completed because of false accusations of embezzlement of funds from the royal treasury against Virupanna which led to him being sentenced to blinding by the king. Before the sentence could be executed, a distressed Virupanna gouged out his eyes and threw them on the wall of the mandapa. The guide pointed out the bloodstains on the wall, which have supposedly not faded even after centuries.

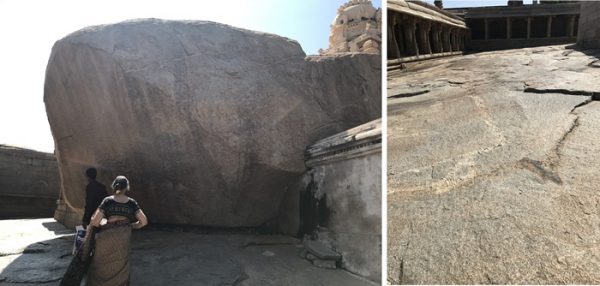

As we walked barefoot on the beautiful hard granite outcrop on which the entire temple complex has been built, the guide told us we did right by visiting in November. “Had you come in the summer this rock would have been so hot that you would have been jumping up and down!”

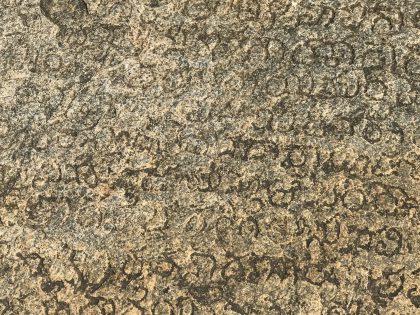

There were many inscriptions in old Kannada (Halegannada) engraved in the rocks all around the temples. I would love to know what they say.

Big boulders and rocky outcrops always remind me of Andhra, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. So many train trips from Delhi to Bengaluru come to mind. The sight of the rocks seen from the train windows would unfailingly inform me that we had entered the Deccan plateau. Without the rocks, these places would lose their identity.

I squirmed when I saw rock quarries on the way to Lepakshi and back. Ugly, mutilated hillsides. Once upon a time, sculptors saw rocks as materials for creating art worth offering to the Gods; today humans are splintering rocks to make ugly buildings.

There was an imposing sculpture of a multi-hooded serpent sheltering a black linga in the Veerabhadra temple complex. The story of how it was constructed took my breath away. A bunch of shilpis (sculptors) had come to the spot at lunch time but were told by one of their mothers that she had not yet started cooking and it would take some time. In those days of slow cooking, one can imagine the wait. If it was me, I’d have gone off to sleep in some cool place. But artistes are made of a different mettle.

The sculptors started working on the big rock near them and within the time it took for the mother to cook food for all of them, they crafted an imposing coiled Naga with fearsome hoods! Here is a perfect example of how real artistes do not create for the sake of money, they do not create in order to get applause; they create because it is play for them; a thing of joy, and there is nothing better they’d rather do!

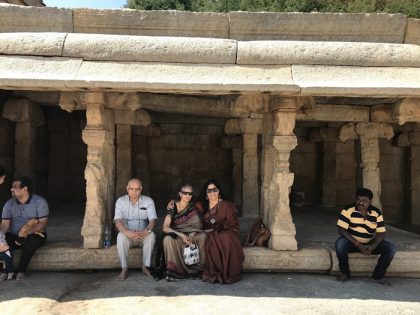

We were feeling a little tired after walking and sat down for a bit in a sheltered hall. The guide immediately smiled and said it was the very place where visitors to the temple rested in earlier centuries. “They did not stay in hotels like you but simply slept in a row in this hall.” He pointed to a stone rod which was used to hang curtains in order to give privacy.

An interesting thing we saw was a thaali (plate) carved into the stony ground with katoris for different dishes exactly like a steel thaali. In fact, there were three of them. I don’t know who ate on them. One could clean the surface, eat and then wash it off for the next diner!

A little away from the temple complex is a colossal Nandi made from one enormous block of stone — again an awe-evoking creation which has been standing for centuries. It is the biggest monolithic Nandi in the country!

I must not forget to mention Jatayu, the pakshi from whom Lepakshi gets its name. Millions of Indians have wept during the scene in Ramayana when Jatayu makes a valiant attempt to stop Ravana from kidnapping Sita Devi but dies in the attempt. It is believed by many that the place where Jatayu fought Ravana and finally fell down wounded is Lepakshi.

While standing near the giant Nandi, I could see a statue of Jatayu on a hilltop but did not have the energy to climb up for a better view. It made me thoughtful about exactly how long Lepakshi had been inhabited. If it was associated with the epic Ramayana then it had to date back to thousands of years.

According to my guide, the reason why the place had been chosen as a site to build a large temple was that it already had ancient Shiva lingas established by Rishi Agastya.

It was time to start back for Bengaluru and I told myself I would be back to gaze at the sculptures in more detail. I thanked our guide and took a picture of him in front of his favorite carving.

Sahana Singh, the author, with her parents

Just outside the temple, I saw these two structures that simply did not fit in with the spirit of the architecture of the place nor the ethos. Clearly, the damage has not ceased even after the Bahmani barbarism.

This article was first published at medium.com.