Why Kashmiri Hindu Parents Stopped Telling Bedtime Stories To Their Children?

The phone rang. My wife, Nidhi, was on the line. We were at a refugee camp for Kashmiri Pandits and staying with some of the children and their parents.

“Rajat, the children do not want to go to sleep. They have shared many incidents from their life and now they are asking me….,” my wife’s voice became blurred as I heard a loud laughter.

Earlier in the day, the Kashmiri Hindu girls had shared with us their growing up in a small and congested room with no privacy. They had shared being mocked by residents around the camp who called them ‘campwalas’ (those living in a camp) and passed nasty comments. They talked of being discriminated against in their schools, market for being refugees.

“Please stay here for a night if you want to understand what we go through everyday.” Nidhi and I had decided to spend a night after their request. Nidhi decided to share a room with some of the girls, I with the boys.

The thought of going back to our hotel’s comfort after a long and tiring day and a grueling workshop was alluring but their appeal had held us back.

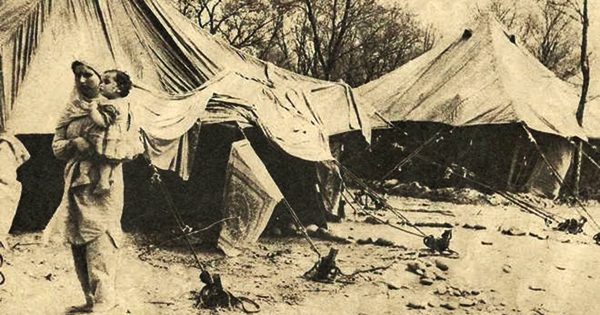

The camp surrounded by a brick kiln throwing fumes wasn’t exactly a dream place to spend the night but little did we realize it will teach us a lesson we will never forget.

“What are they asking you?” I asked her. “Can’t you tell them they have school tomorrow and need to sleep? We do that to our own child every day,” I told her.

“They are pleading with me, asking me tell them a story as a condition for going to sleep. I told them that uncle will tell you one tomorrow but they are saying call uncle here and ask him to tell us right now. One of the mothers is saying they haven’t seen this behavior before.” Then she asked, “Aren’t the boys doing something similar?”

“They are fast sleep,” I told her. “We discussed cricket, Sachin Tendulkar and why Indian cricket team is not in form and the gym they have built up. That was the end of it.”

My mind went through the day’s workshop in slow motion. Our team of psychologists and art therapists had conducted a workshop. The children had expressed many themes, their families running away in the middle of the night, their fear that they will be raped (the slogan that blared from mosques was that leave your women behind in Kashmir to create Pakistan) and their humiliations of being refugees in their own country, I thought as I walked towards their room.

I had thought a story or two would suffice. I couldn’t have been more wrong. After exhausting my stories of ‘panchatantra’, stories from the epics, they had fallen asleep as we switched of the lights and I went back. Two of the girls had laid their heads on my wife’s lap during the story telling. Some of the mothers had stayed awake watching their daughters’ unusual request.

One of the Kashmiri Hindu mothers shared they had always kept the lights on while they slept. Darkness was terrifying for the children and even the families. Almost all families slept with the lights on.

Why do we tell bedtime stories to our children? Bedtime stories are a universal feature of mankind and are rituals followed across all cultures. They have been there since the beginning of human civilization. It is a ritual that as much helps children as it does to parents. Parents want to give their children something to last them through the dark night of separation. We want our children to feel safe and loved and cared for. We impart our inner selves during those moments of story telling to say the world is a safe place for them to grow up. When there is a silence and stories stop from parents, children know something is wrong. They guess, surmise and find out and create a meaning that the world is not a safe place to be.

That is why story telling is one of the first things that parents stop during a war or after a mass exodus as a refugee. They stop telling children stories and they go to sleep terrified often having nightmares and dreams. Massive trauma disrupts the normal processes of our mind by flooding us with affects and experiences that cannot be contained and they turn the world of stories upside down.

The historian Haydon White once said that a narrative or story telling is as much about culture as it is about humanness. Story telling is considered by social scientists as a tool that translates knowing into telling and the way a culture transmits its values to the next generation. Story telling teaches the child the capacity to organize his inner world.

The next day we asked some of the Kashmiri Hindu mothers why they had stopped telling stories to their children. “Yes, we did tell stories when we lived in our homes in Kashmir but ever since living in the camp we stopped. What story do we tell now?” one of them asked.

“There are two stories here. One is of where the world was a safe place once upon a time and things happened predictably. The present one is where we are alone after facing atrocities, of rape, murder and loss of home.”

As that morning progressed many women shared stories of being raped themselves. As Nidhi listened to narratives of trauma after trauma we realized the women had been silent about it.

“Why didn’t you speak up?”

“When we were running away, one of the police officers told me, “Go and lodge your case in India. This is Kashmir. If you try to lodge a case you will be raped again,” one of the woman told her.

“What about the men?”

“The men carry a guilt and feel ashamed they had to run away and couldn’t stop the attackers. They know they couldn’t protect.”

The generation that followed the exodus carried those horrors within them. They passed it on to the next generation on whom fell the task of healing their parents and grandparents. They felt a loss of not just their homes but some whose bodies were violated. This healing may take generations.

I had asked one of the Kashmiri Hindu parents when will they tell stories again, she had said after Article 370 is over and we go back to our homes with dignity. The first step in healing is Justice.

For the generation that ran away, their stories became fragmented, dissociated and got lost. They began to keep secrets of what they went through. Whether it was sexual assault or humiliation of families running away, it happened for only one reason. They didn’t belong to the faith of the majority and refused to convert as a condition for staying back in their homeland.

Will the Kashmiri Hindus once again tell stories to their children now that Article 370 is over and abrogated? Will they build stories of resilience, of hope and courage that will tell them the world is a safe place for their children and that India cares for them, assuring them of a world where they will never have to run away from their homes again?

Will the Kashmiri Hindus of future add a story for their children and grandchildren to describe what happened on 5th August 2019, a story of hope and new beginning? A world where they can imagine living with respect and dignity as equal citizens? A story that could lessen the horrors of 19th January 1990 and the years after that. We may not be able to restore to them what they have lost, but we can say there is Justice and Hope and the world hasn’t forgotten them.

Link for author Rajat Mitra’s book ‘The Infidel Next Door’ and email for overseas orders: bookclubofindia@gmail.com.

Featured image courtesy: Pinterest.

Dr. Rajat Mitra

Latest posts by Dr. Rajat Mitra (see all)

- Sengol: Rebuilding History with the Sacred Symbol - October 23, 2024

- Will the ‘Veer Bal Divas’ Usher a New Era for India? - October 23, 2024

- Dogs and British Empire; A Legacy Followed Till This Day - October 23, 2024