Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar: 1st to Land Mi-171Vs inside Siachen Glacier in 2000; An Interview

We are safe because the Indian Armed Forces comprising of the Indian Army, Indian Navy, and Indian Air Force have been protecting us. Post independence, India fought five major wars – four against Pakistan (1947-48, 1965, 1971, 1999) and one against China (1962). India’s victory in the 1971 war against Pakistan led to the creation of Bangladesh. The wings of the Indian Armed Forces played instrumental roles in India’s victories.

Besides, India undertook several successful operations; one worth mentioning was Operation Meghdoot. After Pakistan started tourist expeditions in the early 1980s in the Siachen Glacier claiming sovereignty over the region, India countered and retaliated with Operation Meghdoot in April 1984. This successful operation led India gain complete control over the Siachen Glacier, spread along 70 km and its tributary glaciers. Pakistan’s attempt of holding sovereignty over Siachen Glacier three years later, i.e. in 1987 and then again in 1989 failed. In this part of the country bordering Pakistan, Siachen Glacier is the point where the Line of Control between India and Pakistan ends.

Helicopters in the IAF play an effective role in transport and utility operations in addition to carrying out attacks. These have become synonymous with search-and-rescue missions and transport in high altitudes. To quote the official website of IAF on helicopter fleet, “The IAF’s helicopter fleet has steadily increased in numbers over the past few years, blossoming from a handful of U.S. types in the 60s to over 500 French, Indian and Soviet built types. The pride of the force is, undoubtedly, the Mi-26 heavy lift helicopter which has been operated by No. 126 HU with outstanding results in the mountains of Northern India. The bulk of rotorcraft are Medium Lift Helicopters (MI-17/MI-17IV/MI-17V5 and Mi-8s) well over two hundred of these types serving in helicopter units throughout the country, playing a vital logistic support role. Induction of the latest machine, the Mi-17 V5, is a quantum jump in our Medium Heli-lift capability in terms of the avionics, weapon systems as well as its hot and high altitude performance. Medium Lift Helicopters of IAF are operated for commando assault tasks, ferrying supplies and personnel to remote mountain helipads, carrying out SAR (Search and Rescue Operations) and logistic support tasks in the island territories, Siachen Glacier, apart from armed role.”

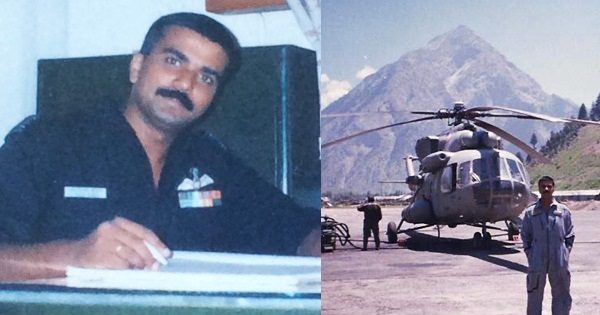

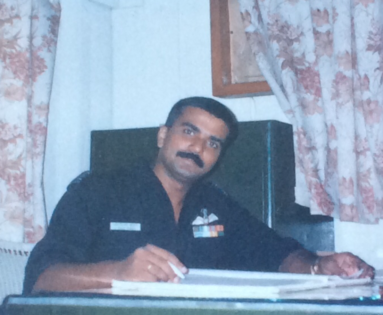

MI-17IV is a ‘helicopter gunship version, powered by two Klimov TV3-117VM turboshaft engines’. Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar of the Indian Air Force was the first to land Mi-171Vs inside Siachen Glacier in the year 2000, a year after the Kargil War. The landing happened on a temporary helipad at a density altitude of 17,500 feet. Sivamohan landed the Mi-171V helicopter almost 5000 feet above the certified limits. Thereafter, he undertook several landings of the Mi-171Vs here.

A permanent helipad was constructed near Kumar post at a height of about 16,000 ft some 15 years later. With border issues an almost humdrum affair, this would not only augment airlift capabilities for troop support and casualty evacuation but also facilitate supply of fresh food to the soldiers deployed for long at high altitudes. Besides, to quote The Hindu, “Helicopters play a pivotal role in sustaining the troops deployed at the height of 20,000 ft on the Siachen Glacier where temperatures plummet to minus 50 degrees in winter.”

My India My Glory team connected with Squadron Leader Sivamohan Vinod Kumar, now retd, to document his experience in landing Mi-171Vs inside Siachen Glacier. He was part of Op Rakshak (counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism operation), Kargil War operations, and more IAF activities in the Jammu & Kashmir high altitude Himalayan sector. Currently, he is working in civil aviation and has been flying various types of helicopters in the oil and gas industry worldwide. He is qualified on 8 different types of helicopters. He served as Director in an international aviation company. Squadron Leader Sivamohan Vinod Kumar has an active flying career of 30 years and more than 12,000 flying hours to his credit.

Here is an excerpt of the interview of Squadron Leader Sivamohan Vinod Kumar taken by Manoshi Sinha, Editor, myindiamyglory.com:

Manoshi Sinha: You nurtured dreams of operating north of Kargil and of wanting to be known as a glacier pilot of the Indian Air Force. Please share with us a glimpse about your journey to the imposing terrain of the Himalayas.

Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar: I completed my training in 1991; after commissioning got posted to Udhampur, 132 FAC FLT, better known as ‘Hovering Hawks’. Our unit had a detachment in Srinagar that was actively involved in counter insurgency and anti-terror operations in active support of northern command based out of Udhampur. The area we covered extended from Bhatinda, Amritsar, Pathankot in the south up to Kargil, Padam and Leh in the north. Those days, Leh had another unit – 114 helicopter Unit called ‘The Siachen Pioneers’. They operated mostly to the glacier in support of our troops. Both units operated the ‘Cheetah helicopters’. I remember feeling jealous of the boys in Leh and flying in the glacier was a sort of badge of honor wherever you went later with Srinagar occupying second position. I made up my mind then and there that I wanted to operate north of Kargil and would want to be known as a glacier pilot.

For a bright eyed south Indian boy, who had never travelled north of Bhopal as my father was a bank employee, the entire journey and posting was a lifetime adventure. Never realizing that was where I would spend more than half my career in the Indian Air Force. Jammu and Kashmir beckoned with its snow-covered peaks and the lush green forests all over. The journey from Jammu in the army convoy to Udhampur got me noticing first hand of the large scale infantry build up and things not being right in the early nineties, when the valley erupted with the first chants of jihad and large scale infiltration from across the border.

After my initial training, I was sent on my first detachment to Srinagar. My senior was a young flight lieutenant, better known as ‘Bond’ for his ‘devil may care’ attitude. I was exposed to the treacherous weather and the constant battle between man, machine and weather operating at those altitudes and the imposing terrain of the Himalayas. My first flight out of Srinagar was a mission to pick up a casualty from Kupwara, where one officer was badly injured when an IED (Improvised explosive device) was set off on an army convoy. A Jawan was martyred and the officer was grievously injured; they were to be evacuated from Kupwara to the army hospital at downtown Srinagar.

Manoshi Sinha: The evacuation task must be challenging, especially when militants there in Kupwara aim at helicopters and aircrafts. Please enlighten us on this episode.

Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar: We were instructed to operate above 10,500 ft, to stay out of small arm firing range. The brief was that either we would fly extremely high above 10,500 feet and carry out spiral descent or fly extremely low staying below tree level and not give the enemy time to react and lock on their weapons due to very short reaction times.

Those days, there were internal reports that the militants had managed to acquire shoulder fired stinger missiles that could easily shoot down aircrafts. That added to the element of uncertainty to the operations and I could sense the nervousness of our senior officers when they carried out our morning briefings.

The flight from Srinagar airport to Kupwara was uneventful and we commenced our descent to land at Kupwara helipad. Bond being an experienced hand by then in the region turned right and started a zig zag pattern descent towards Wular lake as we had overflown Sopur and Uri area, where recent reports of shoulder fired missiles were spotted and the valley was full of AK-47s quite capable of bringing down helicopters or causing significant damage to life. Since Bond was making the approach, I was on a sharp look out for any flashes or any activity on our approach. A landing was carried out and the casualty was brought to the helicopter.

He was about my age – 23 years, with a light moustache, with grey eyes that I have not forgotten till this day. His stomach was covered up in a lot of gauze and when brought inside the helicopter. I placed a reassuring arm on his shoulder and tried a smile, which was returned with an effort to smile, through the significant pain that he was under. Once the casualty was loaded into the helicopter along with a medical assistant, we took off. While departing the helipad at around 400 feet I saw multiple flashes from a house about half a km to the left of where we took off from. I told Bond of what I saw and we decided to drop the plan of vertical climb to above 10,500 feet to set course to BB Cantt helipad, where the casualty was to be dropped. Ignoring the standard operating procedure, we climbed straight towards Srinagar overflying once again the Wular lake.

Once we thought we had cleared out of the danger zone, we checked all operating parameters of our helicopter and could not notice any damage visible to our helicopter, because i was positive that it looked like someone shot at us from behind a house as we were climbing out of Kupwara helipad. Once in cruise, I turned around and looked at the young captain, who had his eyes closed due to the pain probably. On the Cheetah helicopter, we have what we call a collective friction on the floor of the helicopter, which is used to tighten or loosen the controls. I was asked to fly the return leg and make the landing at BB Cantt helipad, which was now inside the heart of Srinagar city, which again was considered a hot bed of militant activity. Bond told me to stay away from the city and do my descent across Dal lake and Shalimar gardens. After tightening my collective friction nut, when I raised my hand, I noticed fresh blood on my flying glove which was beige in color and the blood was fresh. I looked around at the medical assistant travelling with the casualty and noticed that he was still. I was praying for that brother officer from the bottom of my heart wishing that he should hang on. He had been bleeding all the while.

We landed at BB Cantt. helipad where ambulance and all medical services were waiting for us. Bond looked frozen and said this does happen. When we landed back at Srinagar airport, the chief operations officer along with the chief engineering officer were there to meet us, when we shut down. They had received information that a total of about 60 rounds were fired at us, when we were getting airborne from Kupwara helipad. We inspected the helicopter thoroughly for any damage. Probably due to its small size or inaccurate marksmanship by the shooter on the ground, there was absolutely no signs of damage to the helicopter. While doing all this, I was constantly thinking of the face with the grey eyes and the feeble attempt at a smile towards me.

Later in the evening, I called up the Military hospital enquiring about the captain, who was brought in that afternoon from Kupwara, and I was told that unfortunately, he was brought dead to the hospital. I still am not sure, if he died in our helicopter that too on my first official mission in the valley.

Manoshi Sinha: The first mission must have left an imprint on you. Please tell us about your further missions in this part of the Himalayan terrain.

Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar: That glove and those eyes from the first mission stayed with me for the rest of my life. I later did many many missions like that one, in much more treacherous conditions and later came to be known as kind of a veteran of the valley as I ended up spending 4 years flying all over the area up to Leh and down south to Suratgarh. My first mission remained one of my most emotionally draining ones flown in Operation Rakshak. I left the valley in 1995 after almost 1800 hours of flying those conditions.

Manoshi Sinha: You also operated in the Kargil sector including Siachen. Please enlighten us. At such high altitudes and freezing cold, our jawans posted there undertake the most challenging roles of protecting the border. Please also enlighten us about your experience of evacuation missions from the Siachen Glacier sector.

Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar: Post 1995, I was enjoying my tenure in the Northeast and was now posted in Guwahati in 118 HU ‘The Challengers’. Once again I was proud to have been operating in one of the most prestigious helicopter units of the IAF, also one of the first units to operate the Mi-8 helicopters that previously had taken part in the 1971 Indo-Pak War with Mi-4s.

Life was going on quiet in the unit when news came of infiltration of Pakistani soldiers and militia along the Dras -Kargil sector, starting from Mushkoh in the south , all the way up to Batalik in the north. I had been battle hardened in that sector and Jammu-Kashmir-Ladakh had always remained a first love in the service. As May-June carried on and we in 118 HU were sitting far away from all the action shackled as we were.

My contribution that time was high altitude trials of missiles for assessment if we could successfully use armament at those altitudes against the intruders. We were launched twice from the eastern air command to the northern sector and once airborne at night to position to the western sector as there were talks of outbreak of full-fledged hostilities with our western neighbor. We were told to return after getting airborne due to some confusion at Hq level. When news came that Mi 171V helicopters have been pressed into action, me and two of my juniors who had operated in Kargil and knew the area well discussed possible options available with us. We also heard the news of one helicopter lost in Pak firing during the assault on Tololing peak by ‘Nubra Warriors’ formation headed by ‘Chinky Sinha Sir’. I had known both the pilots personally and was a personal loss.

My ex flight commander was now in air headquarters. He spoke to me on the second week of July and said that he is moving me to the northern sector along with 4 more pilots of 118 HU as they needed high altitude experienced pilots and that the IAF is planning to induct new helicopters and was looking for experienced pilots in the region.

On 26 July 99, Kargil War was declared over. Three months later after the war, I was on my way to Jammu 130 HU ‘The Condors’. That unit was given the task of inducting the latest acquisition of the IAF. The upgraded Mi-171V. My unit was operating the Mi-171Vs at that time and was back up to the ‘Nubra Warriors’. Not being able to take direct part in the operations was bugging me at the back of my mind. I was thrilled to be going back to the part of the country that I loved most and the tremendous sense of satisfaction and adrenaline rush that came along with the knowledge that ‘you are right at the forefront of the IAF’s efforts’.

The country had just recovered from the Kargil intrusions and we got busy flying troops and air maintenance from Kargil and Padam. I was over flying Batalik, Dras and Mushkoh sectors. The aftereffects of the war were still visible on the icy rocky heights. The black marks on the mountains made by mortar shots and missiles fired in anger at enemy positions by our jaguars, Mig 21s and importantly the Mirage 2000s with their laser guided bombs, were visible. The army-built bunkers and to prevent further future intrusions was busy fortifying our positions that had to be air maintained by sorties out of Kargil. The weather used to be often cloudy and as we say, clouds, mountains and helicopters are a deadly combo and if you happen to be caught in it at the wrong time, it can be lethal.

After the Kargil conflict, the IAF and Army were very clear that by cutting off the Srinagar highway, the target of the enemy was to cut off the supply lines to Leh and Siachen glacier. Because India occupied the strategic heights in Siachen overlooking the Saltoro range south of the Karakorum pass. The glacier had Indian presence from Indra Coll in the north right up to the base camp established in the Nubra valley at the mouth of the glacier.

The army was deployed at various posts inside the glacier and was maintained by the Cheetah helicopter. The biggest enemy at those heights were the extreme weather and severe body illnesses caused by the heights and extreme cold. The Cheetah helicopters of ‘Siachen Pioneers’ were often called in to evacuate the boys who suffer from extreme frost bite, resulting in gangrene (where the only option many times for the doctors is to cut off the affected body part to save the life Of the soldier). Many cases would be of Pulmonary Edema caused due to water formation in the lungs, causing it to collapse. This in most cases if not recovered quickly would be lethal. All the air evacuation and landings inside the glacier take place at helipads situated at heights ranging from 16,000 ft to 19,000 feet. Any operations above 10,000 ft was required to be carried out by taking oxygen. The Cheetah being a light helicopter and being extremely manurable and powerful for those altitudes were highly suited for the operation, even though they too were operating right up to the flight envelope. To put it simply, no helicopter was designed for regular take offs and landings at those altitudes. The air efforts had been going on since 13 April 1984 with the help of Cheetah helicopters of Indian Air Force and Indian Army, ever since the launch of Op-Meghdoot.

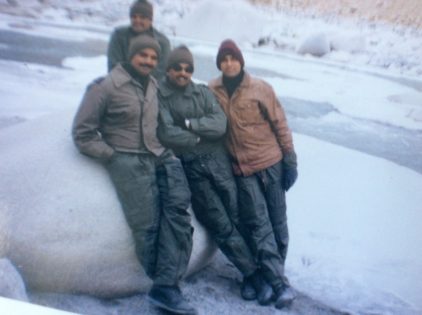

Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar at Self-Base Camp

Manoshi Sinha: Were the landing of Mi-171V helicopters inside the Siachen Glacier challenging? We would like to know about your journey towards being the first to land Mi-171Vs inside Siachen Glacier.

Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar: Back at our home base in Jammu, there was an animated discussion between the senior commanders of the station that they had been requested by the higher ups to look at the feasibility of landing the Mi-171V helicopters inside the glacier. There was a loud laughter in our aircrew room when one of our seniors came and broke the news that there was going to be an attempt to land the Mi-171V helicopters inside the glacier.

To put this in perspective, the IAF and Indian Army had lost many helicopters due to either weather conditions or machines unable to perform at those altitudes. Almost all accidents occurred while landing or taking off from the glacier. The Mi-171Vs were carrying out air drops of rations, armament etc. to the posts inside the glacier. The helicopter used to take off from base camp at an altitude of 12,000 feet, climb along the glacier upwards up to 19,000 feet and return back after air dropping the load at pre designated drop zones inside the glacier. Compared to the Cheetah that is 1950 Kgs in weight, the Mi 171V weighs 12,000 Kgs. That is about 6 times heavier. The Cheetah had been known to have landed at density altitudes of 25,000 feet. Whereas the Mi-171V had a service ceiling of 18,700 feet. Service ceiling means at the highest attitude it can operate legally, and the highest permitted landing altitude was 13,100 feet. So, basically, we were allowed to land and take off from the mouth of the glacier situated at 12,000 feet and that precisely was the reason, no landing was ever considered inside the glacier because it simply was outside all the operating parameters of the helicopter.

It was just out of a whim that I walked up to the flight commander and requested that I be allowed to attempt this landing and I thought it was possible. The image playing in my mind, at the time when I said this was ‘Siachen Pioneers’ carrying out the first landings inside the glacier back in 1984, as part of Op-Meghdoot under similar circumstances when no one before had attempted a landing at such heights and that was to drop two soldiers and that was the commencement of air operations in Siachen glacier because of the strategic importance it holds for the protection of Ladakh and Kashmir.

My flight commander at the time had a peculiar knack of making things simple with a smile and said, “Chalega chalega. Sahi hua tho ok.. galat hua tho laat zaroor and probably end of your career.” He asked me to start studying the performance graphs and give a report to him, which I did, with a detailed study. I was told to be ready but was not told where or when the attempt would be made.

I proceeded for my next detachment to Thoise where we were positioned. The service issue sleeping bag along with multiple quilts wouldn’t keep the cold out and the ‘bukhari’ being coal needed to be put out every evening before going to sleep. Breakfast mostly was Maggi and parathas or puri at base camp. We were busy with air maintenance task and during those days the army task was so high that the helicopter was started up at 0600h in the morning and was shutdown at 1800h back at Thoise. Effectively we had flown 12 hours non stop due to the spiraling backlog due to the glacier shutdown owing to long spells of bad weather.

All tea breaks and lunch was in turn in the cockpit that the gunner used to get from the army unit. Since, we had nothing else to do, we all used to love to be out there to complete the task because we were never sure of the next bad weather phase. The Mi-171V being a large helicopter needed a large radius of turn and I identified that probably the only place where we could land the Mi-171V with any accuracy would have been at the mouth of glacier that was right opposite to ‘Kumar’ helipad. This was a tri junction inside the glacier where it flowed down from the Chinese side towards Karakorum pass. I did notice some activity by our troops in the area but never could have a good look at each pass due to the intense concentration required to stay out of white out conditions while operating inside the glacier, especially during cloudy conditions when it was difficult to maintain your bearing of which way is up or which way is down . It was so easy to get disoriented and fly into the mountain.

That day, we were told there was a helicopter flying in from home base of Jammu and all of us would eagerly wait for such helicopters, as some of us would get replaced and go back to meet our families or some of the wives would sent home cooked food , pickles etc., which had equal rights for all present in the detachment. I normally used to be flying the first helicopter every day out of Thoise to take on the initial loads being the senior most on the detachment. I used that as a privilege to be able to get back if the tasks finished earlier.

A message was received that I was to stay back and wait for a briefing from the Chief Operations Officer at Thoise and a clearance had been obtained for us to carry out the trial landing inside the glacier, where the army had beaten up the snow . The incoming helicopter had couple of senior officers from command. After sending off the other helicopters to base camp, we waited. They arrived around 1000h from Srinagar. I was asked some questions on the feasibility of what we were being requested to do. My plan along with my crew was to carry out the landing empty at the flattened space at the tri junction opposite Kumar helipad. The biggest worry was that this helipad was situated at a density altitude of 17,500 feet, which also was the maximum operating altitude certified for the machine. I was attempting to land the helicopter almost 5000 feet above the certified limits it had operated before.

Manoshi Sinha: I am now the more eager and excited to know about your experience of landing the Mi-171V inside Siachen Glacier at almost 5000 feet above the certified limits – the first in the history of the Indian Armed Forces . Please narrate in detail.

Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar: While we were walking out of the briefing room, we were told, ‘By the way, the Indian Army expects you to bring back around 200-300 kgs of empty fuel barrels from the helipad as part of the conservation attempts .” That was not a request, it was a command! My only option now was to reduce the fuel loads and go with bare minimum fuel. We arrived at the landing site at the correct altitude. At those altitudes, the helicopter controls become extremely sluggish and every action or movement of the helicopter needed to be well thought of and measured. One small error would mean us meshing into the ground unable to arrest the rate of descent or having to go around with a risk of hitting the upsloping snow.

Making an approach and landing such a large helicopter with precision can be compared to a surgeon doing a high pressure surgery. One wrong move could spell the helicopter going out of control. Another restrictive factor operating inside the glacier was that we did not have the luxury to do a normal reconnaissance of the landing area as is standard practice when you are landing at a previously surveyed area, because at any moment, upon hearing helicopters, the Pakistanis, could start shelling into the glacier. Once shelling starts all flying would have to be called off. So, I had to land at my first attempt.

Today, when I look back, I remember, my flight commanders’ words – ‘any mistake could be the end of your flying career’. A landing was carried out and to be surprise, the machine still had a margin of power that could have brought in some load. We did not wait long as the army men and our gunner loaded 15 empty fuel barrels into the helicopter. I handed over controls to my co-pilot, quickly stepped out of the helicopter and felt what my army brothers feel day in and day out when they walked on that hallowed space of the world highest battlefield. A smooth departure was carried out as the machine confidently lifted from all the blowing snow from the beaten down flat area marked as the helipad.

A report was sent to command and air Hq that the mission was a success. I went back to my evening rum with my buddies and merrily carried on with all missions entrusted to me with the greatest smile ever since. It was all in a day’s work.

This landing was carried out in October 2000 a year after Kargil operations and that landing proved that the Mi-171Vs could be landed inside the glacier. Today a full-fledged helipad stands proudly as a force multiplier inside the glacier. I wonder what took us 15 years after we sent the trial landing report to build the helipad. We will never know.

A huge salute to Sqn Ldr Sivamohan Vinod Kumar and the Indian Armed Forces! Vande Mataram!! Jai Hind!!!