Decoding the Religious Origins of the Insurgency in North-East India

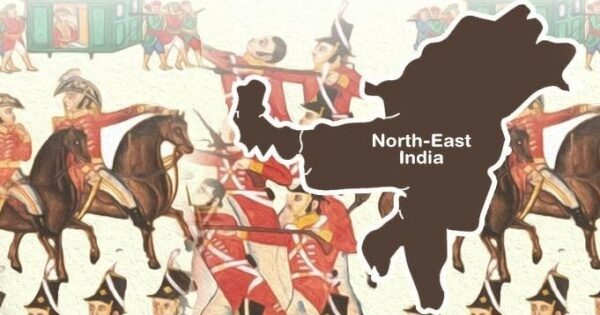

Insurgency in North-East India has covered the entire spectrum of conflict beginning from subversion of constitutionally elected governments to full-scale guerilla warfare carried out overtly or covertly with the support of the local population of the region. It has been a protracted struggle conducted methodically over the years, step-by-step, in order to attain specific intermediate objectives so as to finally overthrow the existing order. Especially in states like Nagaland and Manipur, insurgency has posed a formidable challenge to the established government, calling for effective counter-insurgency measures to defeat the insurgents by bringing about a complete transformation of the existing socio-economic and socio-political order, to maintain the unity and territorial integrity of Bharat.

Leaving aside all benchmarks of what I would say ‘political correctness’, we need to understand the real reasons behind the never-ending insurgency in North-East India. Has it only been the result of economic backwardness or regional economic deprivation as we have been made to believe so far? Is there any correlation between the beginning of insurgency here and the simultaneous decline of Sanatan belief systems? Available research papers and books on this subject have talked about Eurocentric theories of racial conflict, conflict between the core and the periphery, identity crisis, neglect by the Centre, geographical isolation, etc. The subsequent rise of secessionist movements in the North-East with the gradual popularity of a foreign religion in the post-Independence era needs to be understood elaborately in this context.

Genesis of the Problem

It is not to be forgotten that insurgency and secessionism have worked in tandem in this region of the country by first psychologically distancing and then separating people away from their own kinsmen and eventually the entire country. Most importantly, insurgency in North-East India did not develop all of a sudden and in all parts of the region simultaneously. History has been a proof of the fact that whenever Dharmic religious beliefs and faith systems have declined in any area, region or country, separatists soon begin to have a free run. We all know what happened after Sudan was partitioned to create a new Christian country called ‘South Sudan’. For several years, Christian priests from the USA had been converting poor Muslims in South Sudan into Christianity.

As soon as the population of Christians in South Sudan reached 90%, the Church demanded an independent Christian state separate from Sudan. South Sudan continues to be ravaged by severe internal turmoil and political instability even today. Indonesia was also partitioned to create a small Christian country of East Timor, where the Catholic Church is the dominant religious institution. So, the most pertinent questions that arise here are – Who are the real enemies responsible for creating instability and unrest in the North-East, especially the hill states, where a significant chunk of the population identifies itself as Christian? Will Bharat be ever able to defeat these forces detrimental to the security and the safety of her citizens?

The North-East is an indispensable and inseparable part of the philosophical and spiritual heritage of Bharatvarsha and as well as Bharatiya itihasa. The Mahabharata is dotted with several references to Raja Bhagadatta of Pragjyotishpur and his elephant Supratik, who fought on the side of the Kauravas in the Kurukshetra war. The Yogini Tantra and the Kalika Purana too, have numerous descriptions about the land of Ma Kamakhya as the major centre of Tantric-Sakta parampara in Poorvottar Bharat. But, despite always having been an integral part of Bharat, what were the real factors that led several states in this region to resort to a path of armed rebellion against the Indian state just a few years after India’s Independence?

Immediately after Independence, special constitutional provisions were enacted for these states in the name of protecting their “unique tribal culture”. Can we deny the linkage between the rapid growth of Christianity and the subsequent decline of Dharmic faiths in this regard? The reasons behind the introduction of the Inner Line Permit (ILP) System in the North-East under the aegis of the Congress Party led by Nehru, cannot be separated from the context of the rapid growth and proliferation of the Church. The struggle for freedom against the British rule in the North-East was equally against the colonial policies as much as it was against the imposition of a foreign faith, which was not accepted and welcomed by the people of these areas initially.

The life histories and struggles of freedom fighters like U Kiang Nangbah and Togan Nengminja Sangma from Meghalaya, Ropuiliani and Pasaltha Khuangchera from the Lushai hills (present-day Mizoram), Rani Gaidinliu and Haipou Jadonang from Nagaland, etc. are proof enough of this fact. But, the religious demographic character of many states in the North-East has altered beyond reversal. Hardly any traces can be found in today’s date of local deities like Kupenuopfu, Lizaba, and Pfutsana that were worshipped by the Nagas once upon a time. The same holds true for Mizoram and almost more than half of Meghalaya as well. British rule brought about far-reaching social, political and economic changes in the hills of North-East India.

The local population was subject to coercive, territorial authority, which gradually led to an internal re-organisation of the societal structure of the vanavasis. The Chiefs of the community lost their freedom to wage war against their neighbours and order capital punishment, both having serious implications on the law and order scenario. The Christian missionaries, subsidized by the British Government, began their proselytisation activities in the hills along with the introduction of English education. This antagonized many Chiefs in several places in the Lushai hills (present-day Mizoram), Khasi, Garo and Jaintia hills of Meghalaya, and Naga hills, bringing about intermittent conflicts between the people led by their Chiefs and the Church.

Several age-old traditions, customs and modes of worship of the people saw the end of the day after the coming to the scene of the Church. The zawlbuk (similar to a gurukulam) system that was earlier prevalent in Mizoram before the coming of Christianity, can be understood as an apt example of the same. Decline of traditional faiths and belief systems along with the subsequent rise of a foreign faith brings in its wake a certain degree of social discontent, fuelled by a disrupted cultural identity of a community of people. Societal tensions and frictions among different groups and communities of people became quite common since the late 1800s and the early 1900s, when the Church was gradually making inroads in different areas of the region.

The most enduring conflicts in the North-East today are the ones in Nagaland and Manipur (particularly Ukhrul, Senapati, and Churachandpur districts), where rebellions among different groups and communities have lasted for nearly half a century now. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the Naga problem presents the biggest challenge to the security apparatus of the Indian state. The nature of this problem is religious; hence, political solutions to resolve this conflict can at best be short-term. This is exactly where we have messed up. The Indian state has continuously tried to evolve political solutions to contain the insurgency, which, however, haven’t been successful. Several leaders of different insurgent outfits were captured by the Army only to be later released on bail by the civil authorities as an act of compromise. It is disheartening for the Army to see this happen when its own jawans had laid down their lives to capture them.

Christianity & Naga Separatism

The origins of Naga separatism can be traced back to the founding of the Naga club in Kohima in the year 1918 by a group of newly-converted Christian Nagas educated in the Western English system of education. They even submitted a memorandum to the Simon Commission asking the British Government to exclude the Nagas from any constitutional framework that they may be planning for India. However, the protests made by the Naga Club were sporadic till now. The tone and tenor of these protests began to change rapidly with the coming into the scene of Angami Zapu Phizo, popularly known as Phizo. He is still considered to be one of the most dynamic leaders that the Naga separatist movement had ever seen.

It is noteworthy of mentioning here that the Naga separatists came to know about modern warfare techniques in the mid-1940s when India’s North-East was the scene of an intense conflict between the Allied forces on the one hand and the Japanese Army on the other. Phizo, along with some other prominent leaders, fought on the side of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army against the Allies. The war made the Nagas realize that weapons could achieve what negotiations could not. The Naga insurgents would later use the arms dumped in the North-East after World War II to fight the Indian security forces. The 1940s saw the beginning of the struggle for independence in Nagaland and Manipur. This struggle was largely peaceful in nature and their demands had not yet gravitated towards seeking separation from the Indian Union.

Under the leadership of Phizo, it was in the year 1946 that the Naga Club transformed into the Naga National Council (NNC), the precursor of the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN). It was in the early 1960s when groups of Naga and Manipuri insurgents were reported to have gone to China via the Kachin Corridor for free-of-cost arms training under the PLA, aided by Pakistan’s ISI. Trans-border linkages of the North-East Indian insurgent groups started developing within less than 10 years of the country’s independence from the British yoke. Insurgency in Nagaland began soon after the rebels converted into Christianity within just a few years after India’s Independence. They declared an armed revolt under the leadership of Phizo.

The war cry of Phizo’s Naga National Council (NNC) was ‘Nagaland for Christ’. As written by Murkot Ramunny in the book The World of Nagas, it was a Christian missionary named Michael Scott who helped in providing weapons and all other required provisions to these Naga rebels so as to wage a war against the Indian state. In this context, it is not to be forgotten that the arrival of the Christian missionaries in the Naga hills proved to be a critical factor in giving vent to the idea of a single Naga community. The proselytizing efforts of the American Baptist Mission were crucial in linking Christianity inextricably to a cohesive Naga identity, which soon came to identify itself as culturally distinct mainly from the Hindu population of the country. This added a cultural and to some extent a religious dimension to the ongoing resistance of the Nagas.

Phizo had once commented – “We wish to remain within the fold of the Christian nations and that of the Commonwealth. If great Russia and mainland China are proud to feel that they follow the ideology of the German Karl Marx, tiny Nagaland is happy to be a follower of Jesus Christ, whom we have come to believe in as our Saviour.” Broadly speaking, the Nagas comprise around 40 different communities, the major ones including Ao, Angami, Sema, Lotha, Chakhesang, Tangkhul, Chang, Phom, Kengma, Saugtam, Sema, Yimchunger, Mao, Konyak, Zeliangrong, and Rengma. Now, coming to the question of a ‘cohesive Naga identity’ of the NSCN, leaving aside the Tangkhul Nagas of Manipur, most of the communities of Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh like Monpas, Mishimis, Nyshis, Sherdukpens, Apatanis, etc. aren’t Nagas in reality.

However, more and more people, in the recent times, have begun to identify themselves as Nagas more frequently. These are largely the neo-converts who, in due course of time, become mentally programmed to unquestioningly accept their new identity as not only different from the rest but also ‘superior’ to that of any other. The only common element amongst all these so-called “Naga” groups is the American Baptist Church. But, the problem today is no longer limited to Nagaland alone, because the fake narrative of a “separate Christian state” and a cohesive Naga identity propagated by the NSCN is making its presence felt among the Naga population residing in the Manipur hills, Mizoram, and Arunachal Pradesh too.

The main aim of the NSCN is to establish a separate, sovereign Christian state called ‘Nagalim’, unifying all those areas inhabited by the Nagas in North-East India and neighbouring Myanmar. The slogan of the organisation is “Nagaland for Christ”. Its manifesto gives credence to the idea of what can be termed as a ‘Christian theocracy’. It is based on the principle of Socialism for economic development, informed by a Baptist Christian religious outlook. In his book, A Journey Through Insurgent Burma, Bertil Lintner has described the ideology of the NSCN as “a mixture of evangelical Christianity and revolutionary socialism”. Interestingly, the NSCN also has a separate ministry of Religious Affairs to give credence to its idea of a separate Christian identity and Christian nation.

The NNC held a referendum in the year 1951, claiming that 99% of the Nagas supported Independence for Nagaland. In order to evade arrest, Phizo left the Naga hills in 1956 to fight for an independent Naga homeland from foreign shores. He travelled through present-day Bangladesh (then Eastern Pakistan) and Switzerland to finally arrive in London in the year 1960. Under the pressure of the Baptist missionaries led by Nehru’s blue-eyed boy, Mr. Verrier Elwin, the secular Congress Government at the Centre under Nehru accepted all the demands of these rebels. In 1971, the NNC was banned by the Government of India under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967.

On November 11, 1975, the Shillong Accord was signed between the Central Government and a section of the rebel NNC leaders and the Naga Federal Government. This Accord soon proved to be the main bone of contention between the Christian Naga separatists and the Indian state. It was because the signatories to this Accord accepted the Constitution of India and agreed to surrender their weapons by joining the Indian national mainstream for talks and negotiations. Opponents of this Accord who refused to surrender had set up a new insurgent group called the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) under the leadership of Isak Chisi Swu, S.S. Khaplang, and Thuingaleng Muivah.

A significant point to be noted here is that this new group, formed in the year 1980, was launched from bases inside Myanmar. But, very soon, internal rivalries among different clans of the Nagas (especially between the Konyaks and the Tangkhuls) led to a split in its organization in the year 1988. This subsequently resulted in the formation of the NSCN (Khaplang) by the Konyaks under the leadership of Khole Konyak and S.S. Khaplang, and the NSCN (Isak-Muivah) faction led mostly by the Tangkhul Nagas under the leadership of Chisi Swu (a Tangkhul Naga from Myanmar) and Muivah. From this time onwards, the war in the North-East was going to prove deadly, because along with arms, drugs soon came into the scene, and they both became entangled with the politics of the Church in due course of time.

Hebron – Where the Bible and the Bullet Converge

Even after the formation of Nagaland, the Christian rebels kept on fomenting rebellion against the country demanding a separate Naga country (Nagalim). Phizo continued to pursue his dream from the British capital city of London where he stayed as a guest of the Baptist Mission until his death in April, 1990. With the passage of time, the NSCN emerged as the most radical and powerful insurgent group fighting for the Naga cause. For those who might not know, there is a small region in Nagaland called Hebron, situated at a distance of around 110 km from Kohima. Dominated by Baptist Christians, Hebron has been named after the town mentioned in the Old Testament. The NSCN (I-M) almost runs a parallel government in Hebron by the name of ‘Government of the People’s Republic of Nagalim’, complete with ministries and a 15,000 strong army.

The organization has its own Parliament called Tatar Hoho within the precincts of a Church in the northwestern part of Hebron. The Tatar Hoho makes its own laws and metes out severe punishments to those who break them. No wonder, entry into Hebron has always been forbidden to outsiders (specifically meaning non-Christians). When young men and women join the NSCN, they swear by the Bible and the bullet that they won’t betray the nation or compromise the security till the last drop of their blood. There exists a conglomeration of several churches in Nagaland popularly known as the Council of Nagalim Churches (CNC) headquartered at Hebron. It not only plays a very important role in the day-to-day socio-political affairs of Nagaland but also exercise an influence in shaping the public opinion of the common Naga people.

Mizo Insurgency

No wonder, after establishing itself as a front-ranking insurgent group in India’s North-East, the NSCN began to provide arms training and other logistics support to other insurgent outfits of the region. Soon thereafter, the first sparks of insurgency flew off in Mizoram towards the late 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, after the devastating Mautam famine had just ended. At that time, Mizoram was just another district of Assam, and its food shortages that initially began with the flowering of bamboos, were ignored by the Central Government as “exaggerated” and “local superstition of the tribals”. Flowering of bamboos was soon followed by the emergence of a large number of rats which destroyed all food crops and forest wealth of Mizoram. The Church played an important role in extending help and support to the innocent and gullible hill people at this moment of crisis.

The Mizo National Famine Front (MNFF) was subsequently formed under Laldenga, who is still adored in Mizoram as one of the state’s mightiest heroes. In 1966, the Mizo National Front (MNF) began as an underground movement for the setting up of an independent Mizo nation. It was because of the complete laxity on the part of the newly independent Indian Government during the Mautam of 1958 that alienated the Mizos and was largely responsible for the MNFF eventually turning against the Centre and the Indian state. Thanks to Nehru’s abdication of his responsibility towards the North-East, the Church was the primary beneficiary of this mess.

The Mizo insurgency lasted from 1966-1986, and in their initial period of successfully fomenting a wave of terror throughout the Lushai hills and its neighbouring areas, the insurgents were able to capture several towns including the capital of Mizoram, i.e. Aizawl, and a radio station. The end of Pakistani support after 1971 led to a weakening of the force and by 1980, the rebels began negotiations with the Government of India for surrender. Myanmar came into the picture from the 1970s onwards when the responsibility for the training of the different insurgent groups of the North-East and providing them with supplies of arms and ammunitions was taken over by the Burmese rebels.

Assam Wakes Up to Secessionism

It was during the same period that insurgency began in Assam in the form of the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) movement as a protest against illegal immigration from Bangladesh, before it transformed itself into armed militancy that sought separation of Assam from the Indian Union. American author Shelby Tucker has written about having met ULFA chairman Arabinda Rajkhowa at the headquarters of the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO), the political wing of the Kachin Independence Army (an anti-Yangon rebel group in Myanmar) at a place called Pajau Bum, during his trek across Myanmar around 1988-89.

Towards the late 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, nearly all insurgent groups in the North-East depended in some measure or the other on the drug trade from across the border with Myanmar to finance their armies. They have established common training camps in both Myanmar and Bangladesh and often work together to ambush the security forces. It was in the year 1985 that the ULFA opened its shop in Bangladesh, setting up safe houses at Damai village in the Maulvi Bazaar district, bordering the hill state of Meghalaya.

In 1990, the ULFA had its Pakistani contacts well in place, and leaders like Munin Nobis (since surrendered) were instrumental in establishing these links. Towards the end of 1990 and early 1991, the ULFA had set up well-entrenched bases inside Southern Bhutan, mainly in the district of Samdrup Jhongkar, bordering western Assam’s Nalbari district. The reason for choosing Southern Bhutan as a base by the ULFA, and later by the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) and the Kamatapur Liberation Organisation (KLO) was because of the fact that this region was not subject to proper policing by the authorities, was densely wooded, and was located just across the border from Assam.

Besides, Bhutan had a small army and limited capabilities initially to launch counter-insurgency offensives against groups of heavily-armed rebels. It therefore served as an excellent staging area for the Indian separatists, for whom it was easy to return to the safety of their camps in the Himalayan kingdom after carrying out violent strikes in the Indian territory. Very soon, the dark clouds of insurgency began to engulf several states of the North-East, but Manipur, Mizoram, and Nagaland in particular.

Drugs Enter Into the Scene

Drug addiction saw a sharp rise here in the entire decade of the 1980s, when opium cultivation in Myanmar and other areas of the Golden Triangle was at its all-time high. Until the end of 1983, morphine was commonly used by drug users in the North-Eastern states, particularly Manipur. But, the trend changed suddenly, and the number of heroin addicts substantially increased among all other narcotic drugs from the early part of 1984 onwards. In 1990, the first case of HIV/AIDS was detected in both Manipur and Mizoram. In Manipur, the first HIV positive case was reported from the blood samples of October, 1989 among a cluster of Injecting Drug Users (IDUs).

From then onwards till now, the epidemic has been continuously spreading its tentacles, especially among the young population in these states, the most common reason being intravenous drug use. The gravity of the situation can be gauged from the fact that the HIV infection rate in Manipur alone increased from 0% to 50% in just one year during 1990-91. This shot up to 80.70% in 1997 (Morung Makunga, Minister of Health, Government of Manipur, speaking in the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Drugs Panel on Drug Abuse and HIV/AIDS, New York, June 9, 1998. [Courtesy: Free Press, Imphal]).

Insurgency in Meghalaya, Assam & the NSCN

Creation of artificially manufactured racial and ethnic divides has been a time-tested tool of the Church to achieve its evangelical designs. In this process, every trace of native culture is being eroded and finally eliminated first through subtle means and if such means do not work, then violent methods are being resorted to. Coincidentally, the period beginning from the mid-1980s and throughout the 1990s when one after the other hill state in the North-East was coming under the influence of the Church, also saw the beginning of ethnic clashes among different vanavasi communities who were living here together since ages. Insurgency soon began to cast its pall over the comparatively peaceful states of Meghalaya, Tripura, and Arunachal Pradesh.

Rudimentary indications of militancy in Meghalaya were detected in 1989 with the formation of the Meghalaya United Movement (MUM), the main objective of which was the creation of a separate nation for the Khasis. In 1991, the Achik Liberation Matgrik Army (ALMA) came into existence with the aim of establishing a separate Garo-land, comprising of the Garo-inhabited areas of Meghalaya, Assam, and Bangladesh. In 1992, two other insurgent groups came into existence, viz. the Hynniewtrep Voluntary Council (HVC), and the Hynniewtrep Achik Liberation Council (HALC), both of which focused on bringing about an armed revolution for complete separation from the Indian Union.

Soon, this enchantingly beautiful part of the country came to be associated with a toxic combine of drugs, guns, and missionaries. Thanks to the legacy of Nehru, much of our energies and attention remained focused on Islamic jihad in Kashmir in the immediate aftermath of the Partition. This is, however, not to downplay the Kashmir question in the larger context of the country’s national security, which has also been equally about saving the Hindu civilisational heritage of the land of Rishi Kashyap. But, in the meanwhile, the pot kept boiling in the North-East, unknown and unheard to many in the rest of the country. This war was going to prove too insidious and deadly to be tackled by the Indian state in the years to come.

The argument that we have been fed repeatedly by the Leftist academia is that the North-East is a land of ethnic heterogeneity and increasing polarisation along ethnic lines has been chiefly responsible for the rise of insurgent movements and other conflicts. This has been done in order to conceal the reality of religious demographic change and the nature of the problem that is certainly not an “ethnic” one. With the NSCN (Muivah) group extending its militant-cum-evangelical activities beyond the borders of Nagaland including the Naga-dominated districts of North Cachar hills in Assam, it is very important that we look at the entire North-Eastern region as one unit as far as security issues are concerned.

It needs to be mentioned here that the N.C. hills district of Assam, particularly the Jatinga Valley and the Barail hills, has a significant geo-political importance from the strategic and security points of view. It provides a safe corridor for the extremist groups of Nagaland, Meghalaya, Manipur, and Assam’s Barak valley to reach Bangladesh. The NSCN has territorial ambitions in the N.C. hills and nearby Karbi Anglong among the Zeliangrong group of Nagas comprising of Liangamei, Rongmei, Zemi, and a few others residing around Haflong, Mahur, and Maibang areas. This is crucial in the fulfillment of its sinister design of the establishment of a ‘Greater Nagaland’.

Insurgency in Manipur & Tripura

In Manipur, the rapid spread of Christianity in the hills was subsequently followed by bitter clashes between the Kukis and the Nagas on the one hand and the Kukis and the Paites on the other, since the beginning of the 1990s. In 1997, clashes broke out between the Kukis and the Zomis, resulting in an undocumented number of fatalities and large-scale internal displacement of population. As the years passed by, several militant groups, each claiming to represent specific groups and communities, and more often than not, multiple outfits claiming to represent the same community (e.g. there are about nine different groups claiming to represent the Kukis), cropped up in the state.

Significantly, almost all of these insurgent groups have a viable presence in the Christian-dominated hill districts, especially Churachandpur that shares a border with Myanmar. Even a few valley-based outfits, such as the United National Liberation Front (UNLF), the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and the Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP), have secure bases in Churachandpur. No wonder, Churachandpur has always been one of the hotbeds of militancy in Manipur.

Mizoram was undergoing a direct conflict between the newly-converted Christian Mizos on the one hand and the Buddhist Chakmas and the Hindu Reang community on the other. Tripura, in the meantime, witnessed direct conflict between the vanavasi (‘tribal’) population and the non-vanavasis (non-tribals), led by the National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT) that seeks to secede from India and establish an independent Tripuri state. In an article titled Hindu Genocide in Tripura, Aravindan Neelakandan has clearly written that the Baptist Church of Tripura is not just the ideological mentor of the NLFT, but it also supplies the NLFT with arms and ammunitions for the soldiers of the holy crusade.

The religious institutions of the Jamatiyas of Tripura who have resisted Christian conversions have been the foremost target of the rebels of the NLFT. It has also been responsible for mindless killings and unimaginable violence against Hindus (especially the Bengali Hindus who migrated from Bangladesh on the ground of religious persecution) during the long period of rule of the Left Front in Tripura. Many such incidents were, however, never reported in any media. In April 2000, the secretary of the Noapara Baptist Church in Tripura, Nagmanlal Halam, was arrested with a large cache of explosives that he had purchased with “love offerings” and “gifts to further the message of Jesus Christ”

Halam later confessed that he had bought the arms illegally and was supplying explosives to the NLFT for the past two years to bring about the Kingdom of Jesus on the earth that would be ruled with a military hand. Few months later after this incident in the same year, a Hindu spiritual leader named Shanti Tripura was executed in cold blood by ten evangelicals of the NLFT. They justified the assassination by claiming that they feel “marginalised” in front of the existing majority, indirectly referring to those Hindus who refuse to convert. An active participant in the insurgency of North-East India, the manifesto of the NLFT clearly says that it wants to expand what it describes as the ‘Kingdom of God and Jesus Christ’ in Tripura.

The organisation and functioning of the NLFT (currently designated as a terrorist organization by the Government of India) has served as a model for other evangelical Christian terrorist outfits, such as the Manmasi National Christian Army (MNCA), which was charged with forcing Hindus to convert at gunpoint in the year 2009. Seven or more Christian radicalised youths belonging to the Hmar vanavasi community, all dressed in black with a red cross on their back, along with arms, assault weapons and rifles, had visited Bhuvan Pahar in Silchar of Assam’s Barak Valley and pressurised the local population (around 700 Hindu families, and also consisting of a significant section of non-Christian Zeliangrong Nagas) to convert to Christianity.

When the locals refused, the rebel leaders desecrated their temples (around 8) by painting symbols of crosses on the walls with their own blood, claiming that it represented their living ‘warrior God’. Later, the Sonai Police, along with the 5th Assam Rifles, arrested 13 members of the MNCA, including their Commander-in-Chief. Guns and ammunitions were also seized. It may be noted here that Haipou Jadonang, the Hindu Naga leader and freedom fighter, had worshipped Bhagwan Vishnu and another local deity called Tingkao Ragwang at a cave in the Bhuvan Pahar. Hence, this cave is considered as a sacred spot by the Zeliangrong Nagas who worship Bhagwan Vishnu as the chief deity of welfare and all-round prosperity of men and other living beings. In the Zeliangrong Naga religious pantheon, Vishnu is known by different names such as Monchanu, Bonchanu, Bisnu, Buisnu, etc.

NDFB & the Bodo Movement

In Assam, the 1980s was also the period of the beginning of the movement for a separate and ‘sovereign’ Bodoland in the areas north of the Brahmaputra, under the leadership of the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB), an armed Christian separatist outfit, that was first formed in the year 1986 led by Ranjan Daimary. This marked the beginning of insurgency in the Bodo-dominated areas of Assam, which have substantially impinged upon the territorial rights of other communities in Assam. It was reported that during the 1990s, the NDFB established 12 camps along the Assam-Bhutan border and used the forests of southern Bhutan as a safe hideout.

The Bodo Accord of 1993 attempted to bring to an end years of arson, violence and instability, and also sought to identify areas where the Bodo population exceeded 50% as ‘Bodo Areas’. These areas were to be brought under the direct administration of the Bodo Autonomous Council (BAC). However, an adverse consequence of this provision has been the recurring organised ethnic cleansing in those areas where the Bodos do not yet constitute 50% of the population. The failure and subsequent collapse of the BAC notwithstanding, Bodo leaders, drawn either from political or community-based organisations or insurgent factions, have participated in these movements. Their targets have mostly been the security forces and those vanavasi communities who came from outside Assam, to work either in the coal mines or as workers in the tea plantations.

Between 1996-1999, several deaths were reported and large-scale internal displacement of population occurred due to prolonged ethnic clashes between the Bodos and the Santhals on the one hand, and the Bodos and the Oraons on the other. Since the time of its inception, the NDFB has categorically opposed the settlement of any population of non-Bodo communities in the Bodo-inhabited areas through a series of well-planned attacks on vulnerable areas and its residents. E.g. it had unleashed large-scale attacks against the Santhals, Mundas, and Oraons settled in different areas on the north bank of the Brahmaputra, during the 1996 Assam Legislative Assembly elections that subsequently led to the formation of the Adivasi Cobra Force, a rival militant group.

Demographic Change & the Role of China

In the recent times, the unabated inflow of illegal migrants from neighbouring Bangladesh has compounded the problem further. Over the years, the demographic pattern in the entire North-Eastern region of India has been changing rapidly. Assam and Tripura are not the only states to have witnessed some of its worst consequences. The other states in the region too, are now beginning to face the heat. If any change of Government takes place in Bangladesh in the near future, in all probabilities, the jihadi elements will have a free run there and it would pose a serious security threat to the North-East. In the most adverse of circumstances, if the jihadi elements and the Maoists manage to establish a strong base here with the help of the illegal migrants, China would then directly come into the picture.

It is a quite well-known fact that a majority of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) cadres operate from Mandalay in Myanmar and Ruili in China, which is situated at the borders of Myanmar. The role of China, both overt and covert, in supporting the insurgent groups of North-East India, can no longer be downplayed. From the supply of money to weapons, China’s role as a proxy in supporting the armed insurgent groups has often come up several times in the past during high-profile investigations into cases of weapons and arms seizures. Facilitated by the Chinese military, these groups have been using the routes from Myanmar and Bangladesh to smuggle drugs so as to earn easy money for their survival. The inter-linkages between and among the different insurgent outfits based in Manipur and Nagaland as described in a few of the above paragraphs is also not to be overlooked.

References:

- Kumar, R. & Ram, S. (2013). Violence and Terrorism in North-East India. Arpan Publications, New Delhi.

- Lintner, Bertil. (1990). Land of Jade: A Journey Through Insurgent Burma. Kiscadale Publications, Cambridge University Press.

- Ramunny, Murkot. (1988). The World of Nagas. Northern Book Centre, New Delhi.

- Sinha, SP. (2009). Lost Opportunities: 50 Years of Insurgency in the North-East and India’s Response. Lancer International.

Featured image sourced from Study IQ Education YouTube channel on a video by Dr Mahipal Rathore.

Dr Ankita Dutta

Latest posts by Dr Ankita Dutta (see all)

- Sakti Worship in North-East India: Historical, Cultural Perspective - July 27, 2024

- Insurgency in Manipur and Demand for a Separate Kuki Homeland - July 27, 2024

- Manipur Crisis: Exodus of Manipuri Hindus from Their Homeland? - July 27, 2024