Stone Age Seafaring Migrations from Indus Valley to Europe and Pacific Ocean Islands

Worldwide Mesolithic – Neolithic Seafaring Migrations from the Indus Valley: A Paradigm Shift in Ancient Migration Theories

The Mesolithic Era covers differing time spans in different parts of Eurasia. It originally included post-Pleistocene,pre-agricultural material in northwest Europe from about 10,000 to 5,000 BCE, but material from the Levant (about20,000 to 9,500 BCE) is also became labelled Mesolithic.

The Neolithic Era “[…] was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 10,200 BCE […] in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world and ending between 4,500 and 2,000 BCE.”

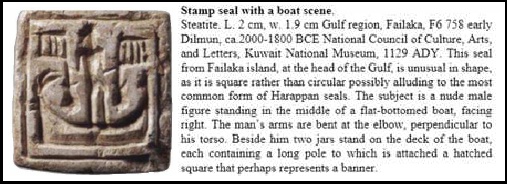

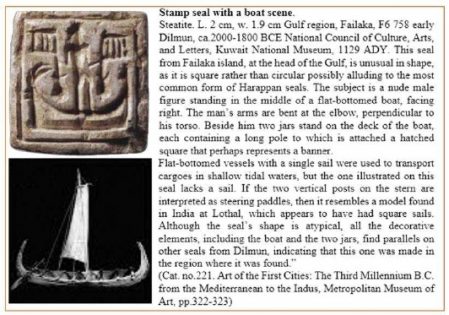

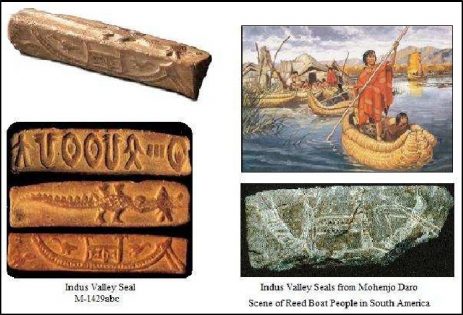

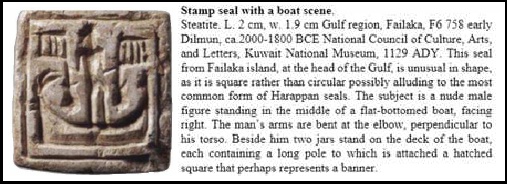

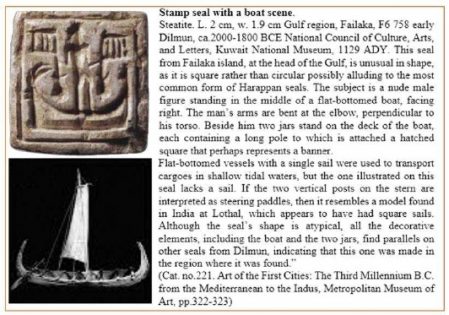

Frontispiece – Gulf Region Seal, Indus Valley Culture Style

Based on language, archaeogenetic and archaeological data, this hypothesis proposes that over an extended period of time, between 9,500 and 3,350 years ago, large segments of the urban,agricultural, river-faring and seafaring population of the northwest delta of the Indian subcontinent – the Indus Valley or the Sapta Sindhu region, described in the Rigveda (RV 7.36.6) as सत संधू “Seven Rivers” – left their homeland in migratory waves. They were driven by:

1. A natural human inclination to “look for other shores”.

2. A number of large natural catastrophes, and the various diseases that resulted from them.

These multiple group migrations went into three main directions, following 3 distinct routes (hereafter called Route 1, Route 2, Route 3):

Route 1

Migrations over sea and along the coasts to coastal European lands: through the Red Seato the Mediterranean lands (including northern Africa), and subsequently via the Strait of Gibraltar to the North Sea’s coastal lands, and from there to the Scandinavian and Baltic Sea coastal regions.

Route 2

Migrations over land within India to north, north east, central and southern Indian regions, where, over time, the migrants merged with existing populations and cultures. Shore hugging sea migration also took place around India’s mainland coasts.

Route 3

Further east over sea, via Sri Lanka, Central Asia, and even as far as the Pacific Ocean’s archipelagos and the Americas.

Preview of the Three Main Routes; Chart by the author, with assistance from Daniel de França

Note: This chart is based on understandings developed by Daniel de França and Nirjhar Mukhopadhyay and was conveyed to the author by email.

The Eurasian overland routes up-river (e.g. the Danube, etc.) and routes further abroad eastwards via Central Asia,China, the various Pacific Ocean archipelagos and across the Pacific Ocean to the Americas, were most likely, together with their migratory purposes, also serving as trade routes to obtain specific supplies: i.e. ores (copper, tin) for the metallurgical industry, and lapidary supplies for jewelry (bead) production.

This hypothesis proposes that throughout their migrations, which altogether may have taken around 6,000 years, the migrants took along with them from their original homeland a number of social, cultural and industrial skills and aspects of the Indus Valley Civilization, which most importantly included their Sanskrit based language – even as it changed over time into various dialects and eventually grew into the various Indo-European as well as Polynesian languages.

Route 1. Ancient Seafaring from the Indus Valley to the Coastal European Lands

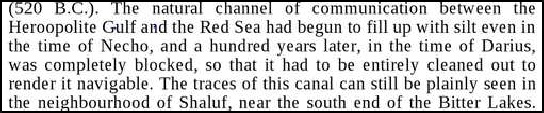

Over time, initially using reed-bundle river boats, a number of Indus Delta population segments took a westerly direction from the delta’s southern shores of the Indian Ocean, using improved seaworthy reed vessels, and after passing south of the Arabian Peninsula, they sailed(and/or rowed) on via the Red Sea through the Suez region (then mostly a channel or strait (not a canal as it is now, as during that period much of that area was inundated due to post-glacial sea level rise) to the insular and coastal areas in and around the Mediterranean.

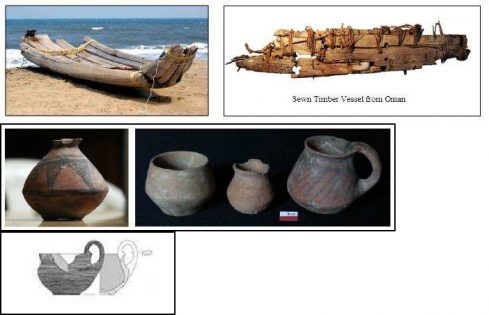

When arriving at coasts (e.g. the Levant) where no reed was available for repairs, new shipbuilding techniques (curved woven together cedar tree trunks, and later, sewn together planked hulls) were invented and applied.

After settling for periods of time on their newly found coasts, many of these ‘Out of Sapta Sindhu Migrants’ and/or their progeny traveled on and passed through the Strait of Gibraltar, after

which they went around the Iberian Peninsula where they left a number of settlements This included what is now Basque territory. From there, after they also left settlements behind on theFrench, Irish and English coasts, many migrants and/or their progeny, sailed through the English Channel to the North Sea’s many islands (now the Frisian and German islands, and the islands and peninsula of Denmark).

Subsequently, between 3,500 to 2,000 years ago, also after leaving settlements behind, many migrants and/or their progeny also sailed to the shores of Scandinavia and eventually many of them arrived on Northern Europe’s Finnish and Baltic Sea coastal areas (e.g. Lithuania).

Route 2. From the Indus Valley into North, Northeast, Central and South Indian Mainland Areas

Other population segments, possibly more sedentary and learned, migrated within India from the Sapta Sindhu Valley to northern (as far as what is now Gandhara), northeastern, central and southern Indian regions.

This topic will be dealt with in an upcoming expanded version of this hypothesis.

Route 3. Further East Over sea via Sri Lanka, even as far as the Pacific Ocean’s Archipelagos and the Americas

The further east over sea migrations via Sri Lanka, into East Asian coastal areas, as far as the Pacific Ocean’s archipelagos such as Polynesia and even into the Americas will also be dealt with in an upcoming expanded version of this hypothesis. Independent researcher Mrs. U. Ringleb writes in her paper East Indian Influence in Polynesian Culture:

“…it is clear that Indian traders and navigators penetrated Southeast Asia in the pre-Christian era: evidence from the Rig Veda shows that there was considerable maritime voyages and trade going on during and perhaps long before the Indus Valley civilization.”

She lists and describes in a detailed manner (65 pages) the lexical word transference between Sanskrit and Polynesian. She writes:

“The cognate pairs span a vast area of human life, ranging from religious andsocial structures to ordinary every-day life. Some of the terms related to natural phenomena are often associated with characteristics of deities. These lexical borrowings indicate contact between the Sanskrit speakers and ancestral Polynesian societies prior to or during the Polynesian expansion from Indonesia [author’s emphasis]. This contact seems to have covered a rather broad area of life,including the borrowing of the names or attributes of deities or spiritual entities who were believed to meet specific needs, e.g., in agriculture, war, or navigation,areas of secret knowledge such as astronomy and religion, as well as a wide range of terms used in daily life. The range of borrowed terms indicate the presence of some representatives of the social and religious elite as well as traders and workers. The Sanskrit terms were phonetically and grammatically simple; they mostly seem to represent what might be called street-level Sanskrit, or Prakrit, and do not reflect the phonetic or grammatical complexity of the elite Sanskrit preserved in political and religious documents and inscription. This fact seems to

indicate that the Sanskrit Polynesian contacts occurred mainly at the working level of the cultures and as a result of trading contacts [author’s emphasis].

Departure from Classical and More Recent “Overland Migration Theories”

As described and proposed in this hypothesis, Route 1 traces a novel pathway (sea-way really), along which the Sanskrit speaking people from the Sapta Sindhu Valley brought their tongue to the European lands where its current inhabitants still speak Indo-European languages.

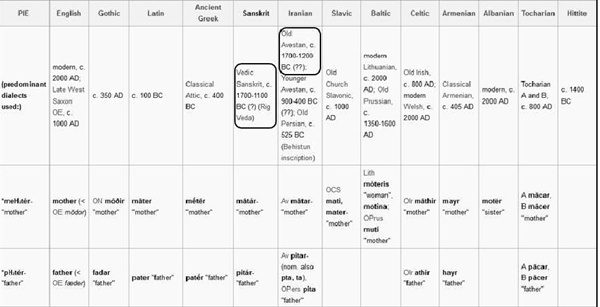

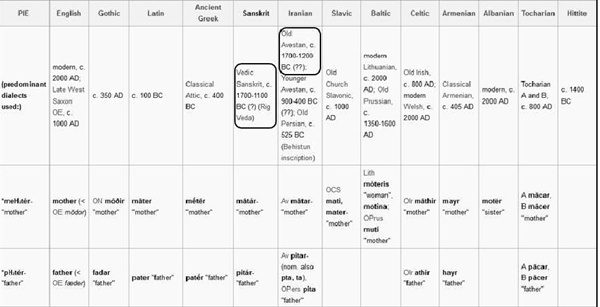

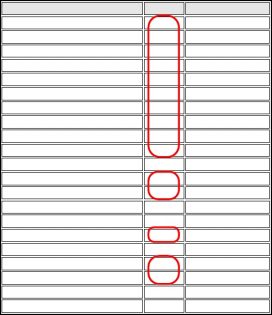

Notice the two marked boxes. The Vedic Sanskrit dates are from 1700 1100 BCE, the Old Avestan dates are from 1700 to 1200 BCE. This table is a partial screenshot from Wikipedia’s article “Indo-European Vocabulary. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_vocabulary#Kinship.) The article lists about 150 of the most fundamental Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) words and roots, with their cognates in all of the major families of descendants. All these words are common use in their respective languages. Studying the table shows that all the other languages’ words listed can be etymologically derived from Sanskrit. The Wikipedia article on Avestan states that according to M. Boyce, the oldest preserved Indo-Aryan language is closely related to Vedic Sanskrit, (Boyce, Mary:1979, Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. pg. 18, Rout ledge) In an interview Prof. Dean Brown states “English, Russian, Icelandic, Greek, are all dialects of a mother tongue that’s spoken widely in India and many parts of the world. Most of the words in English, go back either through the Teutonic, northern European, Icelandic route to the Sanskrit, Vedic, and then [from there] through the Mediterranean route, the Romance route.” (Brown, Dean, 2006) (http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x4ush_thinking-allowed-sanskrit-tradition).

The radical difference between this seafaring, coast hugging and coastal migration hypothesis and a number of current competing overland theories, which deal with (a) the supposed origin of people groupings in continental, or coastal, or inland or insular areas of Europe, and (b) the origin of their languages and their manner acquisition, lies in its departure from any classical and more recent ‘overland theories’ in which it is theorized that language, social and cultural characteristics were spread – presumably – exclusively via the Eurasian Steppe Belt, or the Pannonian Plains (Slovenia), or Anatolia, or the Balkan, or the Caucasus, etc.

A selection of references to a variety of Overland Hypotheses:

1. and ‘consensus theory’ for quite a number of years.

2. Gamkrelidze and Ivanov’s Armenian Hypothesis

a. Gamkrelidze, T. V., Ivanov, V. V.: 1990, The Early History of Indo-European Languages. Scientific American. Vol. 262 no. 3. pp. 110–116

3. Colin Renfrew’s Anatolian Hypothesis.

a. In 1987 he proposed that from around 7000 BCE Indo-European languages began to spread peacefully (by “demic diffusion”) from Anatolia / Asia Minor into Europe.

b. Renfrew, Colin: 1990 [1987] Archaeology and Language – The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-138675-3

4. The 18th century’s OIT or “Out of India Theory” also named “Indian Urheimat Theory”, which holds that India is

the Proto-Indo-European homeland. Various forms on this theme have recently been revived by David Frawley, Koenraad Elst and Shrikant Talageri.

a. Frawley, D., Feuerstein, G., Kak, S.: 1995, In Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India Quest Books (IL) ISBN 0-8356-0720-8

b. Talageri, Shrikant G.: 2000, The Rigveda – A Historical Analysis, New Delhi,ISBN 81-7742-010-0,

c. Elst, Koenraad: 2005, Linguistic Aspects of the Aryan Non-Invasion Theory, The Indo-Aryan Controversy. Evidence and inference in Indian history, Routledge.

Discussion

Route 1 Ancient Coast Hugging Sea Voyages from India to Coastal Europe as far as the Baltic Sea Coast

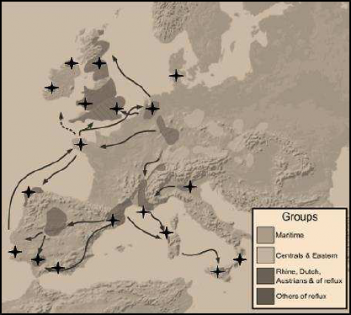

Fig 2. Migration Route 1 from the Indus Valley to European Coastal Lands (The heavy black line traces the route)This chart was originally based on Gamkrelidze and Ivanov’s Armenian Hypothesis. It originally only showed the grey arrows and grey circles that contain the haplogroup Y-DNA labels. (e.g. N -R). Note their presence.

Starting in the Indus Valley and proceeding southwest and northward around the Arabian Peninsula, ‘Route 1’s heavy black line traces this paper’s proposed migration route through the Red Sea, the Mediterranean Sea and, circumnavigating what is now Spain and northern Europe along the North Sea, its trajectory ends up in what are now the Scandinavian and the Baltic Coast countries.

Notice how the black line connects a number faint grey oval shapes (see the straight arrows). These ovals mark areas about which this hypothesis proposes that they represent the very early settlements inhabited by ancient Sanskrit speaking Indus Valley migrants. Ancient haplogroup I mtDNA has been found in all these areas’ skeletons (see Fig 2).

Thus these migrants started the development and spread of the Indo-European Languages through Europe and eventually throughout the whole civilized world. The grey circles and curved arrows on Fig. 2 represent, in my opinion, incomplete views, but it is worthwhile to note them. They represent the Kurgan (Steppes) and Anatolian Hypotheses of how Indo-European languages are supposed to have spread into Europe and Eurasia from Armenia and Anatolia.

a. The grey lines and grey circles represent two current ‘overland’ – more or less – consensus opinions.

b. The heavy black line on the other hand traces this paper’s proposed migration route by sea that was followed by ancient Indus Valley migrants who were genetically characterized by haplogroup I mtDNA (matrilineal) and Y-DNA haplogroup I-M253 (I1a) (patrilineal), migrating from the Indus Valley (currently southern Pakistan and northwest India) as far as Scandinavia and other Baltic Sea lands.

c. The faint grey oval shapes connected by the heavy black line indicate this paper’s coast hugging migrants’ settlement sites. Notice also the settlements in North African Berber lands and what is now Egypt.

This hypothesis is to replace some of the various current migration theories of haplogroupN and R populations to Central Europe as suggested in Fig. 2 by the large grey circles with theirgrey dispersion arrows. Note the hypothesized haplogroup N and R migrations from India to the Levant, some of that I readily accept.

It must be kept in mind though that parallel overland migrations as proposed by the aforementioned Kurgan and Anatolian Hypotheses

also took place, but, I propose, not as exclusively as has been theorized.

The Oversea Route by Seaworthy Reed Bundle Vessels

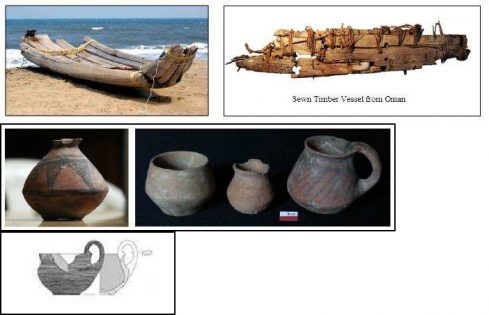

Thus, over time, various Indus Valley population segments took a westerly direction using their seaworthy vessels. Initially those were reed bundle boats (Fig. 14) which were later replaced by interwoven curved log vessels (Fig. 15), and later again by sewn or stitched together wood-board boats, and eventually hulled keel ships.

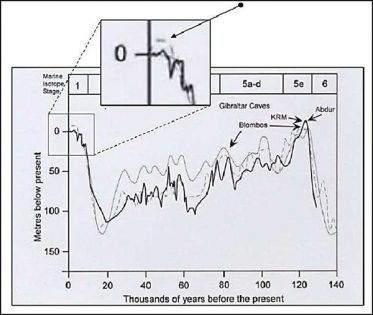

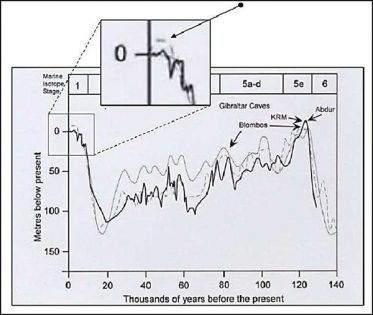

Fig. 3: Historical Sea Levels in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea *. On the chart above we are particularly interested in the grey striped curve (the wavy line between the solid grey and solid black curves). Notice the small square around a detail of this striped curve line near the top of the y axis. Notice also the arrow that points to a tiny segment of that now enlarged curve within the larger square. It illustrates that during a period of about two thousand years – between 5000 and 3000 years ago, sea levels in the regions dealt with in this paper, were about 6.5 meters higher than present. Together with fast moving tidal currents, the described areas (specifically the Suez region) must have been deep enough to navigate through with the flat-bottomed reed ships from the Indus delta.

In support of this hypothesis, with historic data from Red Sea and Strait of Gibraltar sea level measurements (Fig. 3), a joint Saudi Arabia / UK project team* provided the solution to a seemingly unovercomeable problem for the hypothesis at hand – which problem then became serendipitously resolved by… the hand of Mother Nature, that is to say, in fact by ‘ancient climate change’.

A conversation between the author and his son

Manny: What would I do in ‘the days of yore’, if I and my boating companions would be sailing northward up the Red Sea, expecting that we will soon reach the end of that stretch of sea? What then?

Wim: No problem really…

Manny: But there was no Suez Canal then! I mean, how would we, seafaring migrants, reach the Mediterranean Sea and its coastal lands without it?

Wim: Ah, you would be in luck, you know. That Suez Canal would not even be needed. You would be able to reach those Mediterranean shores by boat and…quite easily at that.

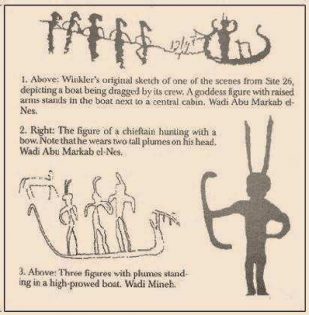

Manny: Of course. I know, we could take the overland route, following one of the wadis to the west into what is now Egypt, and then we could float down the Nile. Eh…If I remember well, that has been done in ancient times. (Fig. 4)*

Wim: True, but actually, even that would not be needed. You see, you would be able to sail straight through what we now would call,

“The Strait of Suez” or, if you will, “The Suez Channel”. Did you know that the sea levels were way higher then,than they are now?! Up to 6.5 meters even!

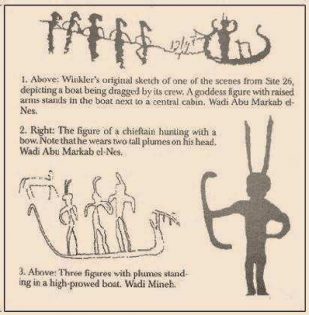

Fig. 4: Through Wadi Mineh and Wadi Abu Markab el-Nes to Egypt’s Delta. From Page 9 in David Rohl’s Book “Legend” *

The Coast Hugging Migration Route

a. After leaving the Sapta Sindhu or Indus delta, the seafaring migrants passed south of the Arabian Peninsula and sailed (and/or rowed) on via the Red Sea through the Suez region which was in those days mostly a channel or strait – not a canal – as much of that area was inundated during that period. (Fig. 3)

b. Then they arrived in most of the insular and coastal areas in and around the Mediterranean Sea.

c. After settling for periods of time on these new coasts, many of these ‘Out of Sapta Sindhu Migrant’ groups traveled on, and before passing through the Strait of Gibraltar, some settled in what is now North Africa’s Berber territory.

d. Subsequently, certain settler groups circumnavigated the Iberian Peninsula to settle in what is now south-west Portugal.

e. They then landed in what is now Basque territory. *

f. From there they settled on the western French, Irish and English coasts. Following migrant groups then sailed through the English Channel to the North Sea’s many islands (now the Frisian and German islands) and to, in those times, insular Denmark, to settle there.

g. Subsequently, between 3,000 to 2,000 BP, the migrant groups also sailed to the shores of Scandinavia, to eventually settle in Northern Europe’s Finnish and Baltic Sea coastal lands.

During these migrations, which altogether may have taken between 2,000 and 3,000 years, the migrants took along with them their Proto-Sanskrit based language (even as it changed over time into various dialects and eventually Indo-European languages). As well, they carried many social and cultural aspects of the Indus Valley Civilization from their original homeland, e.g. tales, tools, pottery, agricultural, stock breeding, metallurgical practices, etc.

Thus, this hypothesis traces a novel pathway (sea-way really) along which Proto-Sanskrit speaking people from South Asia’s subcontinent’s Sapta Sindhu delta brought their tongue to European lands where its current inhabitants still speak Indo-European languages.

(* The Basque language, previously considered to be an ‘isolate’, is considered by Gianfranco Forni to be an Indo-European language which through its Proto-Indo-European (PIE) roots is obviously based on Sanskrit. “It is absolutely unrealistic that Basque was a non-Indo-European language which borrowed over 70% of its basic lexicon (including virtually all verbs) and most of its archaic bound morphemes from neighboring Indo-European languages. The most likely explanation of regular correspondences between Basque and PIE lexicon and grammar is that Basque is Indo-European.”

Forni, Gianfranco: 2013, Evidence for Basque as an Indo-European Language, The Journal of Indo-European Studies, Volume 41, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring/Summer 2013).

Haplogroup I – Charts and Tables *

In this section we deal with “ancient” DNA (aDNA) which means DNA collected from skeletons found in ancient, e.g. mesolithic or neolithic burial sites.

There are two types of DNA: Y-DNA, commonly called paternal DNA (the Y stands for Y chromosomes) which is transmitted from fathers to sons, and mtDNA (mt stands for mitochondrial DNA) commonly called maternal DNA, which is passed from mothers to their children, which together give information about the evolutionary path of the male and female lineage.

The problem with DNA data is that as more and more become available over time, and as different and expanded regions provide newer data (almost daily now) the interpretation of their distribution is very much in flux, thus earlier interpretations of, say, gene-flow become less and less tenable.

When I began research for this paper, only one unofficial mention was made of the presence of haplogroup I mtDNA in a neolithic Indus Valley burial site, which, if I remember well, was either in Dholavira or in Mohenjo Daro.

It was that notion that started my research on this project as I knew that ancient Haplogroup I mtDNA was found all-over in mesolithic and neolithic Europe as well as in North Africa in what is now Berber land and Northern Egypt. (Unfortunately, I subsequently lost that one informal piece of information.)

Nevertheless, it had sparked enough interest in me to proceed with this research as I was looking for the reasons why Indo-European languages were based on Sanskrit.

In the meantime, more genetic data, also from India, became available and thus I gained more confidence in my original idea.

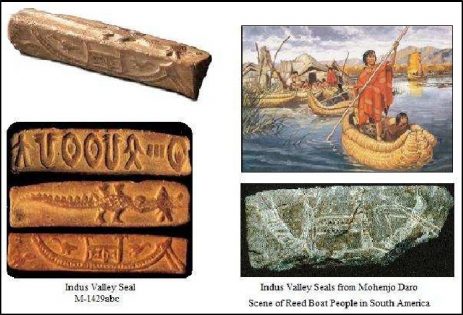

I was at the time also researching the Indus Valley script and through the work of anthropologist Mrs. Suzanne Sullivan ** I became convinced that the language that was spoken in the ancient Indus valley must have been Sanskrit.

The existing hypotheses about the reason for Indo-European languages to be what they were – either coming from the Eurasian steppes, from Anatolia or having their roots in the Near East – never satisfied me as I had, through previous informal research, found that coastal areas in Europe were closer to Sanskrit in their number of words or derivations still being used, and in their articulation, vocalization and pronunciation of words in their respective languages or even dialects.

What especially struck me was that the deeper one went into continental Europe, the less cognates with Sanskrit words were found, as well as less Sanskrit derived words. Granted, these findings were closer to inklings and definitely needed more work, the opportunity for which unfortunately never arose.

(* This hypothesis is also meant to support the hypothesis that Northern European languages have such deep etymological roots in ancient Sanskrit.

Ancient Indian literature, especially the Vishnu Purana, offers accounts of these migrations probably under the rule of King Daksha.

** Sullivan, S.M.: 2013, Indus Script Dictionary, page IV, ISBN 978-1-4507-7061-3)

In any case, in those days I would argue with my linguist friends and query them on why:

“If overland dispersion was the reason why the European languages were INDO-European, how is it possible that coastal lands and islands had their languages or dialects closer to Sanskrit than inland areas?

Things cannot go from good Sanskrit (the source) to poor Sanskrit (the Eurasian steppes) to better Sanskrit (coastal lands) if indeed the dispersion had followed overland routes.

What if the languages were dispersed by coast hugging seafaring migrants from Sanskrit speaking ancient Indian regions?”

To be honest, even to myself, it sounded somewhat naive even if I was convinced that I was in the right track.

Data Tables *

Imagine looking through a pair of binoculars: percentage variations in the lower range (say between 3 and 7%) seem at first sight quite negligible, but when sharpening one’s focus, a quite different, unexpected and significantly detailed picture comes into view.

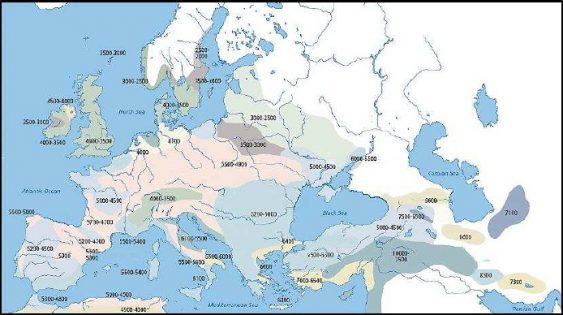

Fig. 6: Current Haplogroup I (ancient mtDNA – maternal) Population Distribution in Europe

We are especially interested in haplogroup I’s presence in the regions marked by the ovals. Notice that the areas are all either coastal or insular and that it includes two Basque regions. Keeping in mind that in this hypothesis it is proposed that Sanskrit based languages and coastal areas are linked, one might wonder why Basque country has Haplogroup I mtDNA and a language which is supposed to be an “isolate”.

Gianfranco Forni (Forni, Gianfranco:2013 **) researched Basque language and established its Indo-European roots, thus the correspondence between Haplogroup I and Basque Indo-European roots is not an anomaly. It stands to reason to conclude that those Basque regions were in antiquity inhabited by migrants who spoke Sanskrit and who left their Haplogroup I fingerprints behind.

(* The data in all the tables of this section come from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_I_%28mtDNA%29

** Forni, Gianfranco: 2013, Evidence for Basque as an Indo-European Language, The Journal of Indo-European Studies, Volume 41, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring/Summer 2013).

For the purpose of this project we are interested in haplogroup I’s presence in the regions marked by the ovals. Studying Fig. 6 we observe that they are all either coastal or insular countries and that some high numbers and some unexpected regions such as Basque regions and the Isle of Skye stand out.

Keeping in mind that in this hypothesis it is proposed that Sanskrit based languages and coastal areas are linked, one might wonder why Basque country has Haplogroup I mtDNA but a language which is supposed to be an isolate, meaning that the consensus opinion is that it has no links with any other language group. Were it not for G. Forni (Forni, Gianfranco: 2013) who researched Basque language and who established that it is indeed an Indo-European language, this would be an anomaly. Being as it is, it stands to reason to conclude that those Basque regions were also inhabited by migrants who spoke Sanskrit and who left their Haplogroup I fingerprints and offspring behind.

Notice that they are all coastal areas. Although other areas are higher in number, they do not necessarily have the same source from where migrants travelled. Thus it stands to reason that some regions had an influx from seafaring migrant and some from land-crossing migrants. The dating of the migrations and their source is very dependent on detailed interpretations.

This table came from more recent reports and it is remarkable that coastal Croatia (approx. 16%) stands out.

In the table Austria and Switzerland are an exception in that they are located in Central Europe and not linked to any European coasts. As the Danube runs through Austria it could well be that the influx of Haplogroup I came from a different direction: perhaps the Black Sea. (See Fig. 1. The light blue line terminates in Austria and Switzerland.)

Carpathian Lemko (11.32%) might have its Haplogroup I sources though from the Black Sea. It is interesting that the Lemkos’ language is an isolate.

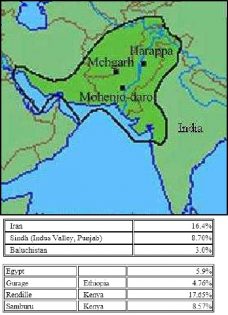

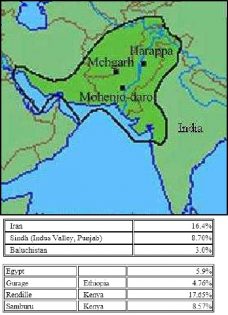

North West India, Current Iran, Pakistan

This table shows the latest data from Iran, Pakistan and Baluchistan. It should be kept in mind that currently Sindh and Baluchistan are part of Pakistan and that the Indus Valley delta extends beyond the Sindh province into India’s North West.

The current Haplogroup I distribution in Iran is 16.4 %, and in Pakistan’s Sindh (including the Baluchistan foothills and plateaus) and Indian Punjab’s regions 11.7 %.

This map is saved from www.bashapedia.pbworks.com Fig. 8: The marked area shows the extent of the Indus Valley Civilization’s cultural influence.

As this hypothesis proposes that the migrant haplogroups I’s source came from the original Indus Valley Culture inhabitants, we should keep in mind that the Indus Valley Civilization’s (also called the Harappa Culture) cultural influence at its most flourishing period encompassed the marked area in Fig. 8.

North and East Africa

The high ancient mtDNA percentages of these four areas may indicate how far the oversea travels went from the Indus Valley, and how the Harappan migrants may have established settlements in Egypt and on the eastern African Coast.

Current European Continent

“The frequency of Haplogroup I may have undergone a reduction in Europe following the Medieval age. An overall frequency of 13% was found in ancient Danish samples from the Iron Age to the Medieval Age (including Vikings) from Denmark and Scandinavia compared to only 2.5% in modern samples.”

~ Hofreiter 2010 *

The quote above tells us about non-modern numbers, and the example shows that those numbers in the past were actually even higher: e.g. for Denmark 13% instead of 5.71%.

“[Y-DNA] Haplogroup I-M253 arose from haplogroup [Y-DNA] I-M170, which appears ancient in Europe. The haplogroup was previously thought to have originated 15,000 years ago in Iberia, but is now estimated to have originated between 4,000 – 5,000 years ago. It is suggested that it initially dispersed from Denmark.” **

The dating that I propose for this coast-hugging, sea-faring ‘Out of the Sapta Sindhu Delta Migration’ hypothesis, is that it began 9,500 years ago, and that it arrived in Europe’s North Sea islands and coastal areas “between 4,000 – 5,000 years ago” (the estimate in the quote above) in – what is now – Denmark, Northern Germany, etc. and that Sanskrit based language elements dispersed from there into the hinter-lands of the European continent.

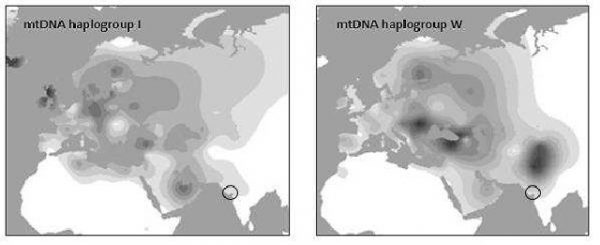

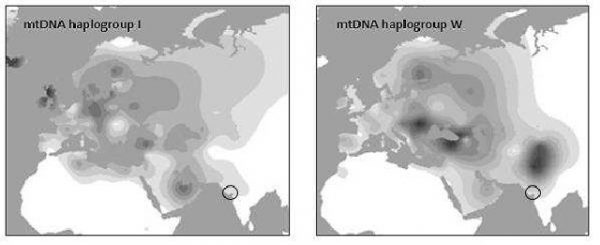

Fig. 9: mtDNA Haplogroups I and W. Note the two circles. ***

Left: Haplogroup I, spatial frequency distribution of haplogroups I sub-clades I1a. Right: Haplogroup W, spatial frequency distribution.

(* Hofreiter, et al.: 2010, Genetic Diversity among Ancient Nordic Populations” PLoS ONE. 5 (7): e11898

** Pedro Soares, et al.: 2010, The Archaeogenetics of Europe, Current Biology, vol. 20 (February 23, 2010), R174–R183. yDNA Haplogroup I: Subclade I1, Family Tree DNA

*** Olivieri A., Pala M., Gandini F., Kashani B.H., Perego U.A., Woodward S.R., et al.: 2013, Mitogenomes from Two Uncommon Haplogroups Mark Late Glacial/Postglacial Expansions from the Near East and Neolithic Dispersals within Europe. PLoS ONE 8(7): e70492. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070492).

Notice in Fig. 9 the faint presence of haplogroups I (the two circles) in the Indus Valley. It might be considered of little relevance. However, as proposed here, consider that from 9,500 years ago on, migrants travelled for various * reasons overland (much of Haplogroup W) and oversea (Haplogroup I) to the Near East, North Africa, Europe and Eurasia (all the shaded areas in Fig. 9), and thus seeded those regions with their DNA and increased their population in those lands, while for reasons of natural catastrophes and calamities (e.g. epidemics **) in Northwest India after the end of the mature phase of the Indus Civilization (2000 BCE) that they did not increase in population in the Indus Valley….

In fact, at some point the whole valley was considered inhabitable. (“Collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization***).

“The current human mitochondrial (mtDNA) phylogeny does not equally represent all human populations but is biased in favour of representatives originally from north and central Europe. This especially affects the phylogeny of some uncommon West Eurasian haplogroups, including I and W, whose southern European and Near Eastern components are very poorly represented, suggesting that extensive hidden phylogenetic substructure remains to be uncovered. [author’s emphasis] […] Thus our data contribute to a better definition of the Late and postglacial re-peopling of Europe, providing further evidence for the scenario that major population expansions started after the Last Glacial Maximum but before Neolithic times, but also evidencing traces of diffusion events in several I and W subclades dating to the European Neolithic and restricted to Europe. [author’s emphasis] *

~ Olivieri A., et al.: 2013,

(* Quote from this paper’s Abstract:

“They were driven by:

A natural human inclination to “look for other shores”.

A number of large natural catastrophes, and the various diseases that resulted from them.”

** Robbins G., Tripathy V.M., Misra V.N., Mohanty R.K., Shinde V.S., et al.: 2009, Ancient Skeletal Evidence for Leprosy in India (2000 B.C.). PLoS ONE 4(5): e5669.,10.1371/journal.pone.0005669

*** “The Indus Civilization flourished between about 2600 and 1800 BCE when it collapsed into regional cultures at the Late Harappan stage. According to Parpola the collapse was due to a combination of several factors like over-exploitation of the environment, drastic changes in the river-courses, series of floods, water-logging and increased salinity of the irrigated lands.”

~ Iravatham Mahadevan

Iravatham Mahadevan, https://www.harappa.com/script/maha1)

A Question

Where did that 13% in ancient Danish samples come from?

If not by inland, overland routes, via what routes did the Haplogroup I migrants arrive in the circle-marked regions of Fig. 6, if not by sea?

Remember my previous queries to linguist friends:

“If overland dispersion was the reason why the European languages were INDO-European, how is it possible that coastal lands and islands had their languages or dialects closer to Sanskrit than inland areas?

Things cannot go from good Sanskrit (the source) to poor Sanskrit (the Eurasian steppes) to better Sanskrit (coastal lands) if indeed the dispersion had followed overland routes.

“What if the languages were dispersed by coast hugging seafaring migrants from Sanskrit speaking ancient Indian regions?”

BTW, the dating also appears to be right, as it indicates that the stone- and iron-age seafaring (as proposed here) migrants took their time!

Map by Aaron J. Hill based on data from Rootsi S., et al.: 2004 *

Fig. 10: Patrilineal Y-DNA Dispersion of Haplogroup I-M253 (I1a) in Northern Europe

Considering Y-DNA Haplogroup I-M253 (I1a), we see that it is most present in Scandinavia, Denmark and Finland thus supporting Hofreiter’s mtDNA haplogroup I data (Hofreiter, et al.: 2010).

(* Rootsi S., Magri C., Kivisild T., et al.: 2004, Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75:128–137, 2004)

Preliminary Conclusions

Route 1

Considering all of the above, one can arrive at a conclusion that, parallel to overland migrations, oversea migrations took place.

Thus, based on percentage numbers only, feasible meso/neolithic coastal-route population migrations can be traced back (backwards in time and voyages taken) from Northern Europe to their original South Asian source:

a. Scandinavia, Finland, the Baltic coast lands and Denmark, the Frisian Islands, the British Isles, Scotland, Ireland and Brittany (Bretagne – a West France peninsula),

b. Basque coastal regions and Spain and Portugal,

c. The Strait of Gibraltar and further east:

o North Africa’s Berber lands and northern Egypt,

o The French Mediterranean coast, the Mediterranean Islands, Italy, Greece, Macedonia, Croatia, the Levant,

d. What is now the Suez Canal region, but was then fully inundated – let me coin it the “Ancient Suez Channel” or “Ancient Suez Strait”,

e. The Red Sea and around the Arabian Peninsula,

f. The Sapta Sindhu Valley and the foothills of current Northern Pakistan and Northern India.

These coastal areas show a varied though significant range of ancient matrilineal mtDNA Haplogroup I percentages (Fig. 9 left), which when combined with the presence of patrilineal Y-DNA I-M253 (I1a) (Fig. 10) is distinct from Haplogroup W mtDNA (Fig. 9 right) that has been found in the areas through which – according to the “Steppe Theory” – overland migrations across mainland and hinterland Eurasia are theorized to have taken place.

When reading the above list from the Sapta Sindhu region upwards (now Lower Pakistan/North-Western India) to Scandinavia, one gets to follow the sea-route that the Haplogroup I seafaring migrants may very well have taken.

Recent Proposals by others (June 9, 2014) about Neolithic Seafarer Migration Routes

For a partial tracing by others of partial sea-faring migration routes see online articles on Science Daily and Phys Org News. *, **

What this hypothesis proposes goes further though than the theory described in both online articles. The following quote gives the gist of those hypotheses.

“Genetic markers in modern populations indicate the Neolithic migrants who brought farming to Europe traveled from the Levant into Anatolia and then island hopped to Greece via Crete and then to Sicily and north into Southern Europe.” *

(* Science Daily, http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/06/140610102041.htm#.U5dQghvx2Go.facebook

** Phys. Org., http://phys.org/news/2014-06-mitochondrial-dna-eastern-farmers-sequenced.html)

Fig. 11: Other Overland and Oversea Routes *

This hypothesis is distinct because of:

* Different original starting-off points – The Indus Valley (the Sapta Sindhu Delta) instead of the Levant,

* Different final arrivals – Northern coastal Europe instead of mainland or hinter-land northern and southern Europe,

* Different haplogroups: mtDNA haplogroups I and Y-DNA I-M253 (I1a) instead of M and R haplogroupings.

Migration routes changed according to global extended-period sea level rises or dips. The levels at certain times were so high (from 6.5 meters higher than current levels, See Fig. 3) that boat people could float (following the current), sail or row through the Suez zone. At other times this was not possible, hence different routes during different time periods. Obviously dating and analysis of Mediterranean sedimentation layers around the Suez zone would be helpful.

“The most significant conclusion – highlights Eva Fernández – is that the degree of genetic similarity between the populations of the Fertile Crescent and the ones of Cyprus an Crete supports the hypothesis that Neolithic spread in Europe took place through pioneer seafaring colonization, not through a land-mediated expansion through Anatolia, as it was thought until now“

(* Phys. Org., http://phys.org/news/2014-06-mitochondrial-dna-eastern-farmers-sequenced.html Fernández, Eva, et al.: 2014, Ancient DNA Analysis of 8000 B.C. Near Eastern Farmers Supports an Early Neolithic Pioneer Maritime Colonization of Mainland Europe through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1004401)

Route 2

Migrations within India from the Sapta Sindhu Valley

to North, North-East, Central and Southern Indian regions.

The Indus Valley’s non-seafaring inhabitants also migrated to various other areas throughout India:

1. Inland boat-people went down as far as Kerala (partially by land, partially coast hugging by boat.)

2. Mostly agrarian groups went up the higher Indus Valley areas and to the foothills of the Himalayas. (I predict that scriptural artifacts will be found, containing a more cursive IVC script, likely hidden inside Buddha statues inside Buddhist caves.)

3. A number of groups migrated to the Ganges areas. (Local stories and legends replaced the Sarasvati river name with the Ganges river name.)

Note: A 5,000 year old settlement discovered in 1957 in Alamgirpur village, Baghpat (UP), is evidence of migration into the Upper Doab region between the Ganga and the Yamuna.

“The settlement marks the eastern most limits [author’s emphasis] of the Harappan culture and belongs to the late Harappan phase, a period starting around 1900-1800 BC when the Indus Valley Civilization, popularly known as the Harappan Culture, began to decline,”

~ Bhuvan Vikram (The Hindu, September 14, 2015)

It was exactly during that period, that Harappan group migrations eastwards from the Indus Delta began. Thus, this settlement was NOT the “eastern most limit” as Mr. Vikram states, but one of the early signs of migrations eastward from the Indus Delta proper.

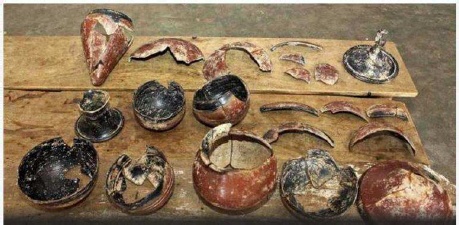

4 Large groups went South overland into central India (where Black and Red Ware pottery has now been found), down deeply into what is now Tamil Nadu, where stories about Skanda/Karthikeya are still being told, and where he is still honoured as a major God.

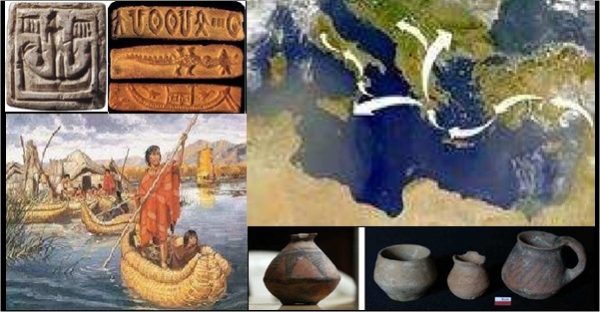

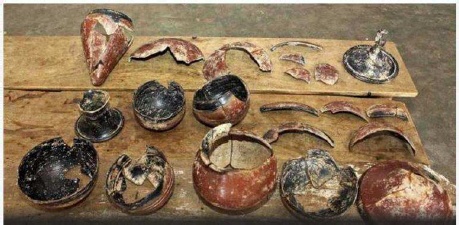

Fig. 12: Black and Red Ware, Krishnagiri, Southern India *

(* The Hindu: http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/iron-age-megalithic-burial-site-found-in-krishnagiri/article7152408.ece?homepage=true?w=alstates#comments)

Route 3

Further East Oversea, via Sri Lanka, even as far as the Pacific Ocean’s archipelagos and the Americas.

This further East oversea migrations to Sri Lanka, into Chinese Coastal areas, as far as the Pacific Ocean’s archipelagos (U. Ringleb, 2016) and the Americas, will be dealt with in in an upcoming extended version of this hypothesis. It is part of the following prediction that evidence will be found.

Predictions

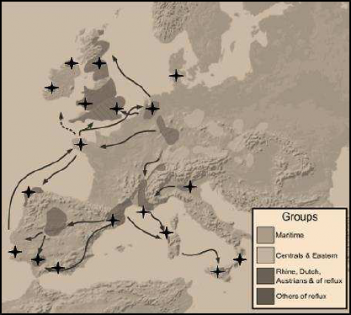

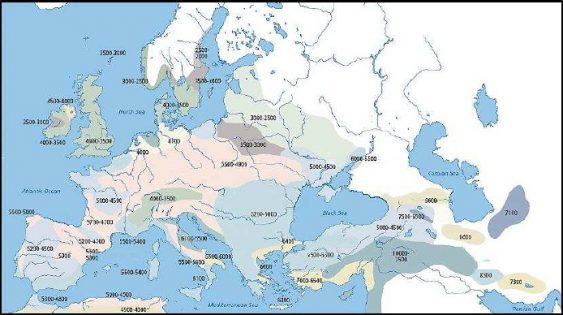

1. It will be discovered that the route of pottery-ware distribution (e.g. Bell Beaker Culture, Corded Ware) differed from what is currently the consensus opinion. Fig. 13 minus the stars represents the current consensus view about the Bell Beaker Culture pottery diffusion.

Part of this hypothesis also proposes that the coastal European regions were earlier areas where Bell Beaker pottery was introduced (lightest grey shading), meaning that the Central Europe and Eurasian received their pottery tradition subsequently. This hypothesis also proposes that Bell Beaker pottery was based on pottery that originated in the ancient Indus Valley.

Chart Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28870457

Stars added by the author. Fig. 13: Bell-Beaker Culture

“Corded Ware culture (also Battle-axe culture) is an enormous Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age archaeological grouping, flourishing ca. 3200 – 2300 BC. It encompasses most of continental northern Europe from the Rhine River on the west, to the Volga River in the east, including most of modern-day Germany, Denmark, Poland, the Baltic States, Belarus, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, northern Ukraine, and western Russia, as well as southern Sweden and Finland. It receives its name from the characteristic pottery of the era; wet clay was decoratively incised with cordage, i.e., string. It is known mostly from its burials.”

~ D. Bachmann *

2. By tracing Indus Valley Culture Painted Grey Ware (PGW), Grey Ware (GW) and Black Red Ware (BRW) migratory movement of Indus Valley migrants will be traced.

3. Etymological linkages will be found between Baltic Sea island names and Indus Valley Civilization words and names.

4. Ancient sunken wreckage will be found in the Baltics with shape characteristics like IVC reed vessels as in Fig. 14.

Fig. 14: Indus Valley Reed Boat Seals

(* D. Bachmann

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_Corded_Ware_culture-en.svg).

5. Stitched-board boat construction will be traced back to Indus Valley rib-less ship construction.

Fig. 15

Left: Bundled Curved Log Vessel (Tamil Nadu, S. India) Right: Stitched Board Vessel (Oman)

Fig. 16: Harappan, from 4MSR, near Binjor, Rajasthan

Fig. 17: Macedonian Grey Ware *

Painted Carinated Cup (FT240) from Kastanás, Level 12 (Jung, 2002: plate 29.312)

8. Submerged cities will be discovered in the Mediterranean Sea which will show evidence of city layouts, culture, burial practices and artifacts that have clear Indus Valley Civilization characteristics. It might even be that ancient skeletons will be retrieved that may still have testable mtDNA and Y-DNA traces.

9. Decorative patterns in the folkloric female dress tradition (e.g. Gandhara) will be discovered as similar or identical across the European coastal lands from Serbia, Croatia, etc. to Finland.

(* Jung, Reinhard, http://www.aegeobalkanprehistory.net/article.php?id_art=4)

10. Tracing the dating of farming (see Fig. 19) along all European and North African coastal and insular areas, it will be proposed that those regions are on a trajectory that coast-hugging seafaring migrants followed and that they, when they went on land, founded settlements that included farming, animal husbandry and crafts such as pottery, metal working, male and female folkloric attire. (Which even today shows up in traditions that can be traced back to Indus Valley culture.)

Chart (Broushaki et al., 2016) Annotated by the author Fig.18: Dating of Neolithic Farming Regions. (Data from Broushaki, Farnaz, et al. 2016)

It is generally assumed that:

“The earliest evidence for cultivation and stock-keeping is found in the Neolithic core zone of the Fertile Crescent region stretching north from the southern Levant through eastern Anatolia and northern Mesopotamia, then east into the Zagros Mountains on the border of modern-day Iran and Iraq. From there, farming spread into surrounding regions, including Anatolia and, later, Europe, southern Asia, and parts of Arabia and North Africa. Whether the transition to agriculture was a homogeneous process across the core zone, or a mosaic of localized domestications, is unknown. Likewise, the extent to which core zone farming populations were genetically homogeneous, or exhibited structure that may have been preserved as agriculture spread into surround in regions, is undetermined. [author’s emphasis]. *

(* Broushaki, Farnaz, et al.: 2016, Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent, SCIENCE sciencemag.org, 2016 VOL 353 ISSUE 6298499)

Conclusion

Rather than overland migrations as proposed by the various overland migration hypotheses, over-seas and coast-hugging migrations took place by seafarers who originated from the Indus Valley and who spoke an early form of Sanskrit, who settled in Europe’s coastal regions as listed below.

Based on language, archaeogenetic and archaeological data, over an extended period between 9,500 and 3,350 years ago large segments of the population of the north-western delta of the Indian subcontinent (the Indus Valley or the Sapta Sindhu region from the Rigveda (Sanskrit सप्त ससिंधू “Seven Rivers”) left their homeland because of a number of natural catastrophes and resulting diseases (leprosy, tuberculosis) that resulted from them.

These multiple group migrations went into three main directions:

1. Migrations oversea to coastal European lands: from Red Sea, Mediterranean and as far as Baltic Sea coastal regions,

2. Migrations within India to North, North East, Central and Southern Indian regions where they, over time, merged with the existing populations and cultures. (Further research data are currently being gathered and analyzed.)

3. Further East oversea, via Sri Lanka, even as far as the Pacific Ocean’s archipelagos and the Americas. (Further research data are currently being gathered and analyzed.)

Thus, based on mtDNA Haplogroup I and Y-DNA haplogroup I-M253 (I1a) percentage numbers only, but supported by etymological data that show that all Indo-European languages find their roots in early forms of spoken Sanskrit, it can be concluded that mesolithic and neolithic coastal-route population migrations can be traced from their original source – from what is now North-West India and Pakistan to Northern Europe:

From the Sapta Sindhu Valley and the foothills of current northern Pakistan and northern India,

Down around The Arabian Peninsula through the Red Sea,

Then through what is now the Suez Canal region but was then fully inundated: the “Ancient Suez Channel or Strait”,

Then to the Mediterranean coastlands:

o Some groups to Northern Egypt and what is now Berber land,

o Other groups to the Levant, Croatia, Greece and Macedonia,

Then via the Italian peninsula and the Mediterranean islands to southern France,

Then around Spain and Portugal to Basque lands

To Brittany (Bretagne – a west France peninsula), Ireland Scotland, the British Isles, the Frisian Islands, the then Danish islands, Scandinavia, Finland and the Baltic coast lands.

The above listed coastal areas show a varied though significant range of ancient matrilineal mtDNA Haplogroup I percentages (Fig. 9 left), which when combined with the presence of patrilineal Y-DNA I-M253 (I1a) (Fig. 10) is distinct from Haplogroup W mtDNA (Fig. 9 right) that has been found in the areas through which – according to the “Steppe Theory” – overland migrations across mainland and hinterland Eurasia are theorized to have taken place. *

(* Originally of course – at least that is not disputed – much earlier populations came to, what is now, India and Pakistan via southern Arabian Peninsula’s coast from what is now East Tanzania and Kenya.

“In paleoanthropology, the recent African origin of modern humans, also called the “Out of Africa” theory (OOA), the “recent single-origin hypothesis” (RSOH), “replacement hypothesis,” or “recent African origin model” (RAO), is the most widely accepted model of the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans. The theory argues for the African origins of modern humans, who left Africa in a single wave of migration which populated the world, replacing older human species.”

~ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recent_African_origin_of_modern_humans

“Currently available genetic and archaeological evidence is supportive of a recent single origin of modern humans in East Africa. However, this is where the consensus on human settlement history ends, and considerable uncertainty clouds any more detailed aspect of human colonization history.”

~ Liu H., et al.: 2006, A geographically explicit genetic model of worldwide human-settlement history. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79 (2): 230–7. 10.1086/505436.)

Bibliography

Ammerman A.J., Cavalli-Sforza L.L.: 1984, The Neolithic Transition and the Genetics of Populations in Europe. New Jersey, Princeton University Press

Bramanti B., Haak W., et al.: 2009, Genetic discontinuity between local hunter-gatherers and central Europe’s first farmers. Science 326, 137–140. 10.1126/science.1176869

Broushaki, Farnaz, et al.: 2016, Early Neolithic genomes from the eastern Fertile Crescent, SCIENCE sciencemag.org, 2016 VOL 353 ISSUE 6298499

Cooper A, Poinar H.N.: 2000, Ancient DNADo it right or not at all. Science. 2000;289:1139

Deguilloux M.F., et al.: 2012 European neolithization and ancient DNA – an assessment. Evol Anthropol 21: 24–37.: 10.1002/evan.20341

Robbins-Dexter M., Jones-Bley K., eds.: 1997, The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles from 1952 to 1993, Washington, DC: Institute for the Study of Man

Elst, Koenraad: 2005, Linguistic Aspects of the Aryan Non-Invasion Theory, THE INDO-ARYAN CONTROVERSY. Evidence and inference in Indian history, Routledge

Forni, Gianfranco: 2013, Evidence for Basque as an Indo-European Language, The Journal of Indo-European Studies, Volume 41, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring/Summer 2013

Frawley D., Feuerstein G., Kak S.: 1995, In Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India Quest Books (IL) ISBN 0-8356-0720-8

Gamkrelidze T.V., Ivanov V.V.: 1990, The Early History of Indo-European Languages. Scientific American. Vol. 262 no. 3. pp. 110–116.

Gilbert M.T.P., Bandelt H.J., Hofreiter M., Barnes I.:2005, Assessing ancient DNA studies. Trend Ecol Evol. 2005;20:541–544

Gimbutas, Marija: 1970, Proto-Indo-European Culture: The Kurgan Culture during the Fifth, Fourth, and Third Millennia B.C., in Cardona, et al.: Indo-European and Indo-Europeans: Papers Presented at the Third Indo-European Conference at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 155–197

Gimbutas, Marija: 1982, Old Europe in the Fifth Millenium B.C.: The European Situation on the Arrival of Indo-Europeans, in Polomé, Edgar C., The Indo-Europeans in the Fourth and Third Millennia, Ann Arbor: Karoma Publisher

Gimbutas M., Dexter M; Jones-Bley K.: 1997, The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe, Selected Articles from 1952 to 1993, Washington, D. C., Institute for the Study of Man

Haak W., et al.: 2010 Ancient DNA from European early neolithic farmers reveals their near eastern affinities. PLoS Biol 8: e1000536, 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000536

Haak, W., et al.: 2015, Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, Nature10.1038/nature14317

Hofreiter M., Serre D., Poinar H.N., Kuch M., Pääbo S.: 2001, Ancient DNA. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:353–359

Hofreiter, et al.: 2010, Genetic Diversity among Ancient Nordic Populations, PLoS ONE. 5 (7): e11898

Jensen J.: 1995, The Prehistory of Denmark. London, Routledge

Kivisild T., et al.: 2006, The role of selection in the evolution of human mitochondrial genomes. Genetics. 2006;172:373–387

Lalueza-Fox C., Sampietro M.L., Gilbert M.T.P., Castri L., Facchini F., et al.:2004, Unravelling migrations in the steppe: mitochondrial DNA sequences from ancient Central Asians. Proc Roy Soc Lond B. 2004;271:941–947

Connan J., Carter, R., et al: 2005, A comparative geochemical study of bituminous boat remains from H3, As-Sabiyah (Kuwait), and RJ-2, Ra’s al-Jinz (Oman). Arab. Arch. Epig. 2005: 16: 21–66 (2005)

Malmström H., Gilbert M.T.P, Thomas M.G., Brandström M., Stora J., et al: 2009, Ancient DNA reveals lack of continuity between neolithic hunter-gatherers and contemporary Scandinavians. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1758–1762

Mallory, J.P. :1989, In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson

Olivieri A., Pala M., Gandini F., Kashani B.H., Perego U.A., Woodward S.R., et al.: 2013, Mitogenomes from Two Uncommon Haplogroups Mark Late Glacial/Postglacial Expansions from the Near East and Neolithic Dispersals within Europe. PLoS ONE 8(7): e70492. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070492

Pinhasi R., Fort J., Ammerman A.J.: 2005, Tracing the origin and spread of agriculture in Europe. PLoS Biol 3: e410, 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030410

Rappaport, Dr. Solomon: early 20th century, The Waterways of Egypt, Volume 12, Part B, Chapter V, page 248. London: The Grolier Society

Renfrew, Colin: 1990 [1987] Archaeology and Language – The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-138675-3

Renfrew, Colin.: 1999, Time depth, convergence theory, and innovation in Proto-Indo-European: ‘Old Europe’ as a PIE linguistic area. J INDO-EUR STUD, 27(3-4), 257-293

Ringleb, U.: 2016, East Indian Influence in Polynesian Culture

https://www.academia.edu/19936307/EAST_INDIAN_INFLUENCE_IN_POLYNESIAN_CULTURE

Richards M., Macaulay V., Hickey E., Vega E., Sykes B., et al.: 2006, Tracing European founder lineages in the near eastern mtDNA pool. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1251–1276

Richards M.B., Macaulay V.A., Bandelt H.J., Sykes B.C.:1998, Phylogeography of mitochondrial DNA in western Europe. Ann Hum Genet. 1998;62:241–260

Robbins G., Tripathy V.M., Misra V.N., Mohanty R.K., Shinde V.S., et al.: 2009, Ancient Skeletal Evidence for Leprosy in India (2000 B.C.). PLoS ONE 4(5): e5669.,10.1371/journal.pone.0005669

Rohl, David M.: 1989, Legend – The Genesis of Civilization, Random House

Rootsi S., Magri C., Kivisild T., et al.: 2004, Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75:128–137, 2004

Sampietro M.L., Caramelli D., Lao O., Calafell F., Comas D., et al.: 2005, The Genetics of the Pre-Roman Iberian Peninsula: A mtDNA Study of Ancient Iberians. Ann Hum Genet. 2005;69:535–548

Shennan S.: 2009, Evolutionary demography and the population history of the European early neolithic. Hum Biol. 2009;81:339–355

Soares P., et al.: 2010, The Archaeogenetics of Europe, Current Biology, vol. 20 (February 23, 2010), R174–R183. yDNA Haplogroup I: Subclade I1, Family Tree DNA

Soares P., Rito T., Trejaut J., Mormina M., Hill C., et al.: 2011, Ancient voyaging and Polynesian origins. Am J Hum Genet 88: 239–247. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.009

Sullivan S.M.: 2013, Indus Script Dictionary, ISBN 978-1-4507-7061-3

Talageri, Shrikant G.: 2000, The Rigveda – A Historical Analysis, New Delhi, ISBN 81-7742-010-0

Tamm E., Kivisild T., et al.: 2007, Beringian standstill and spread of Native American founders. PLoS One 2: e829. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000829

Torroni A., Achilli A., Macaulay V., Richards M., Bandelt H.J.: 2006, Harvesting the fruit of the human mtDNA tree. Trend Genet. 2006;22:339–345

Töpf A.L., Gilbert M.T.P., Fleischer R.C., Hoelzel A.R.: 2007, Ancient human mtDNA genotypes from England reveal lost variation over the last millennium. Biol Lett. 2007;35:550–553

Van Oven M., Kayser M.: 2009, Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E386–E394

Wittle A.: 1996, Europe in the Neolithic. The creation of New Worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

About the author W. J. Borsboom

– Canadian independent researcher, lecturer and writer on archaeo-linguistics and the Harappan Culture’s seals and script.

– This hypothesis was first conceived by the author on October 15, 2013. Additional data were added May, 2014. In April 2015 the hypothesis was provisionally extended (with limited available data) to include China, the Pacific Archipelagos and the Americas

– Mr. Borsboom is the author of “Alphabet or Abracadabra? Reverse Engineering the Western Alphabet” (ISBN 978-1-4602-6230-6), a monograph on the topic of how more than 3400 years ago, the Western Alphabet’s sequence of phonemes (abecedary) was modeled after an, at that time still simple, ancient Indian Pre-Ashokan Brahmi alphabet (abugida)

– From November 2015 to March 2016 Mr. Borsboom was a guest lecturer at 20 venues (universities, colleges and museums) during his 4.5 months lecture tour throughout India.

This post was first published under the title ‘Worldwide Early Holocene Seafaring Migrations from the Indus Valley’ in the peer reviewed Journal ARNAVA (Latest version, 2017).

The following two tabs change content below.

Mr. Wim Borsboom (a Canadian from Dutch descent) is a retired teacher, currently a researcher on Archaeology. From childhood he had deep interests in Hinduism, Buddhism, Eastern Archaeology and ancient languages.